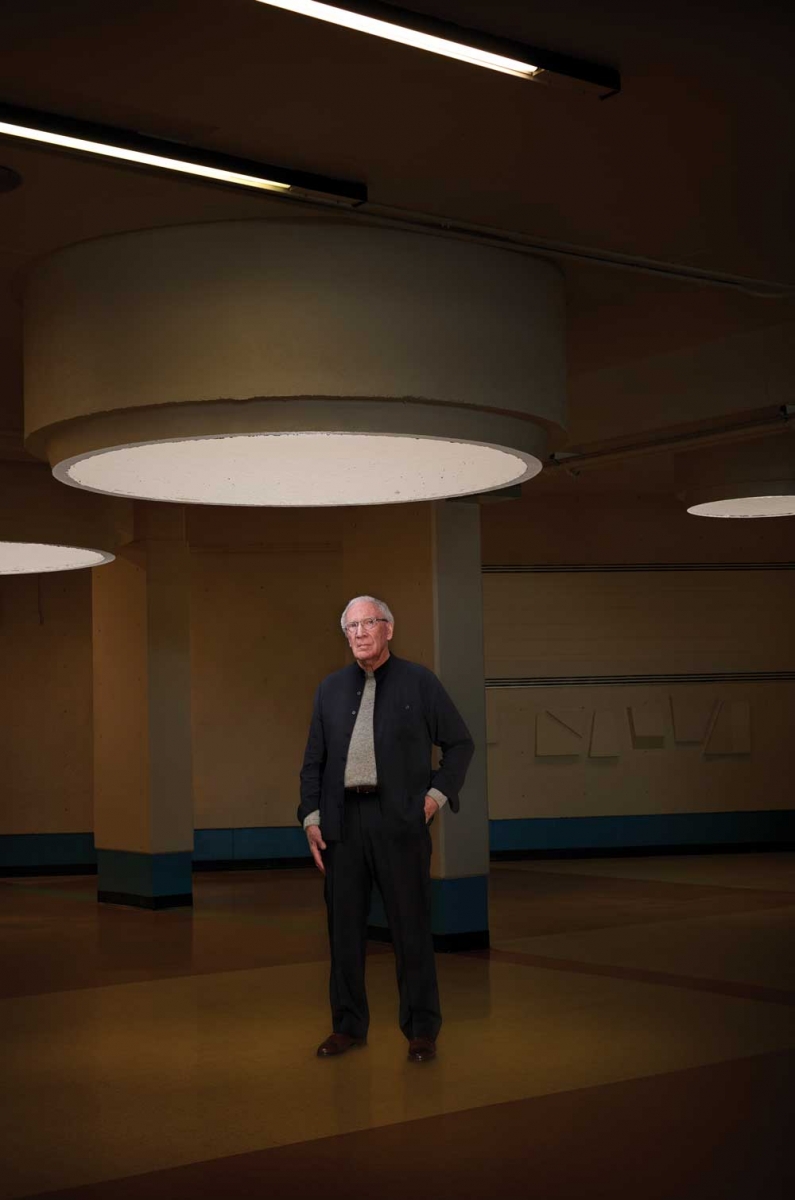

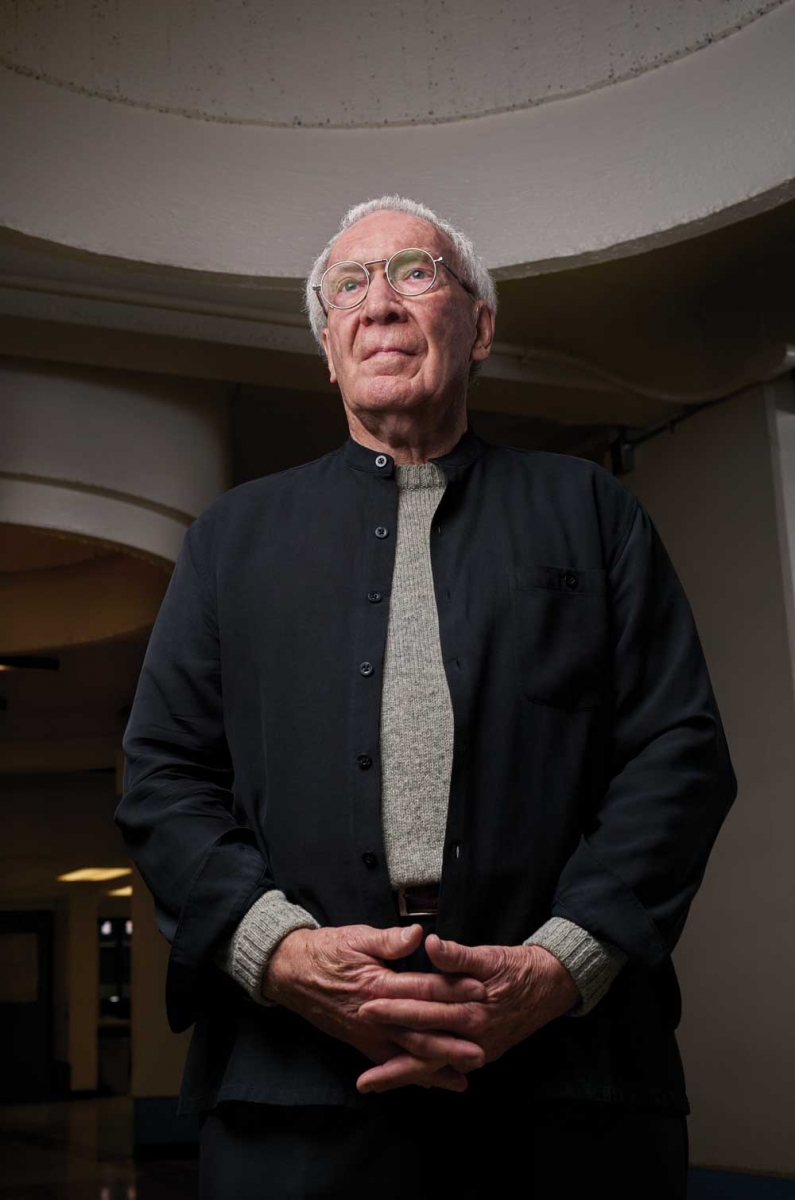

Calgary architect Gordon Atkins at Mayland Heights Elementary School, one of about 25 buildings he designed over his career. Built in 1967-1969, the building was unique at the time in that the height of amenities like drinking fountains and chalkboards were scaled to the students, rather than to the adults.

Back in the 1960s, young architect Gordon Atkins was sitting in the outer office of a potential employer, awaiting a job interview. From his vantage, Atkins could overhear the man talking on the phone. Eventually, he decided to leave.

The man caught up to Atkins in the hallway and when asked why he left, Atkins replied: “I’ve listened to you for 15 minutes; I don’t want to work here.” Atkins’ recollection of the rest of the exchange implies a great reversal of roles, with the employer asking to see his work and then having to convince the young architect that he should accept the job. Atkins eventually agreed – albeit on the condition that the two of them wouldn’t interact over the course of an architecture competition they would be entering. He got the job.

Atkins’ strong personality colours many of the stories the 81-year-old has to tell. In the late 1960s, the Alberta provincial government’s cultural department sent writers and photographers to profile 30 artists and architects in order to create a one-man show about each. One half of the pair assigned to Atkins wrote that she found him very arrogant at first. “Then, by the fifth day, she said it wasn’t arrogance at all, it was confidence,” says Atkins. “My son says, no, she had it right the first time.”

Atkins was born in Calgary in 1937, though his birth parents divorced shortly afterward and he moved with his mother to Cardston, Alberta, a town of roughly 2,200 people at the time, whose only architect-designed building was a Mormon temple (the first built in the British Commonwealth). Atkins’ perspective on the role of architecture has been formed through decades of experience but may also draw from this background. He believes the role of the architect is to provide a functional, spiritual, three-dimensional experience at a level that will bring out positive interactions with the user of the space. “It’s the refined experience translated to people who otherwise would not be able to have that experience,” he says.

A lifelong Mormon, Atkins would go on to twice serve as a bishop of the church in adulthood, however, his religious upbringing didn’t prevent him from getting into trouble as a youth. His early life is peppered with stories like his fall from a 50-foot grain elevator, only to land safely in a pile of grain. “There are at least five times that I should have been dead. Each of those things taught me some real lessons, but I also came to think that with that many opportunities to die, there must have been some reason for me to be around,” he says. “I always have that in the back of my mind, that there must have been something [I was] supposed to do.”

An early proclivity for sketching, and a conversation with his high school principal, helped him decide that calling might be architecture. “The minute [my principal] mentioned architecture – I knew nothing about it, there were certainly no architects in my experience in Cardston – it just clicked, and all I had to do was decide to be, and prove that I could be, one.”

After receiving his bachelor of architecture degree from the University of Washington in 1960, Atkins worked for a few smaller firms in Winnipeg, Seattle and eventually Calgary. He started a firm in Calgary with partners in 1961 and left two years later to go solo.

In 1966, at only 29 years old, Atkins became the first Albertan to win the Massey Medal for the Melchin Summer Homes, a pair of lakeside vacation residences in Windermere, B.C. The medal, a beautifully engraved piece of solid silver given out by the Governor General between 1950 and 1970, was the most prestigious architecture award of its time. Atkins keeps it, along with a number of his other awards, in a bag behind his shoes at the back of his closet. “Obviously the first Massey medal in Alberta was important to me as a young architect,” says Atkins. “But I’ve never been a very good person for displaying things on walls.”

The Melchin homes were only his third project and though his career garnered him a literal bagful of awards, Atkins produced a relatively small body of work – a total of 25 built structures – prior to his semi-retirement in 1995 (the year he stepped away from active architectural practice, though he says he has never stopped working entirely). This number belies the excellence of those projects, however. As architect Graham Livesey writes in his 2005 book Gordon Atkins: Architecture, 1960-95: “The outstanding quality of [Atkins’] work makes it among the most significant work built in Canada from the mid-1960s to the mid 1980s.”

This concentration of quality over quantity seems to stem from his convictions, which led him to leave or reject a number of projects because they would not allow him to practice his trade as he saw fit. When a client told him that, though they liked a design he’d spent two years on, they weren’t going to build it and wanted him to come up with another, he flatly refused. “I said, ‘what you’re saying is that, the last two years of my life, when every moment of my thinking has been focused on this project, you want me to tell myself that I’m wrong about all that, and I should go back and do it again, but not with a new program, not with new problems, but just different, and it’s not possible.'”

Atkins’ concept for the Stephen Avenue open-air pedestrian mall, commissioned by the City in 1968, is another example of the many disputes he had to mediate during his career. In preparation, Atkins spent a month and a half touring and researching similar malls in North America, finding, among other things, that the typical mall surface was an expensive, inflexible tile, not suited to the Calgary project. His solution was to use three-foot, sandblasted, pre-cast concrete slabs, each supported by four adjustable steel jack posts that would be lowered into trenches dug two feet into the existing surface. The elevated slab sidewalks would allow for a hidden heating system to melt snow, facilitate rain runoff and accommodate electrical and mechanical components for future displays or businesses.

These plans immediately raised eyebrows, notably of John Ivor Strong, then chief commissioner for the City of Calgary. According to Atkins, when the business association initially voted in favour of Atkins’ proposal on a Friday, Strong called one business owner and said he’d reverse the direction of 7th Avenue and get rid of their store’s entrance unless they flipped their vote. The following Monday, the concept was voted down.

Other aspects of Atkins’ pedestrian mall were eventually approved – but with a red-brick surface instead of his original concept. Atkins wrote a letter to the City administration saying that he would proceed with the red-brick surface, but refused responsibility for it. He foresaw issues from laying the brick directly on the asphalt, concerns echoed by one of Strong’s own engineers.

Ultimately, the architect had the last laugh. “They did it anyway and after it was done it started to move,” he says. “The doors of the shops along there wouldn’t open because the brick was moving up and down.” When a city commissioner wanted to sue him, Atkins’ letter ensured that had they ended up in court he would have been bullet proof.

The rest of the mall as Atkins designed it was wholly replaced by the late 1980s – one of the many ghosts of his work in Calgary. By his own count, around 20 of his structures are still standing. Of those remaining, he says “there aren’t many that have not been altered in ways that are most unfortunate.” Even Atkins’ former home in Mount Royal, which he had used as a sort of test subject, was demolished in 2013. His son jokes that having the Gordon Atkins name on a structure indicates its imminent demise.

In hindsight, Atkins’ visions for the city offer a tantalizing “what if” scenario – many of his ideas were years ahead of their time. He’s the second-most-mentioned architect in Stephanie White’s Unbuilt Calgary, a book detailing Calgary projects that almost were. Of his 1963 critique of a proposed downtown freeway, where Atkins suggests the City instead transform 7th Avenue into a transportation corridor for buses, streetcars, the continental railway, taxis and bikes, White writes, “what is surprising is how prescient Atkins was and how strong was his vision of a centralized, compact city that used public transit to keep its edges close.”

One of the many stories Atkins has from his working years is about how he had been hired to design a home for a client who contested a number of features that eventually were included, at Atkins’ insistence. Years later, his judgement was vindicated when the client called him up one Sunday. “He said, ‘I’m just laying here on the bed and looking up at that clerestory window that we fought about. Now I see what it is you were trying to tell me, and I love it,'” recalls Atkins. “And so, there are some of those stories that make you think, well, maybe I’ve been right a couple of times.”