This is the Kiyooka Ohe Arts Centre, soon to be a place to study and appreciate art. Right now, it is where Harry Kiyooka and Katie Ohe live, two great Alberta artists who have dedicated their lives to creating art and sharing it with others.

He’s an abstract painter, art collector and art advocate. She’s a teacher who makes kinetic sculptures and prints. They met in the 1960s – they can’t agree on the story of their first meeting – and bought the land in Springbank for their home and studios in 1973. They’re both legends in the Canadian art world, yet few Calgarians outside of the visual arts scene know how great an impact Kiyooka and Ohe have had on art in Alberta.

Both Ohe and Kiyooka were born in Alberta and raised in poor families. Kiyooka, born in 1928, moved from Calgary with his family to a farm north of Edmonton in 1941 during the Second World War. As Japanese-Canadians, the family had faced racism and prejudice in Calgary.

“My father lost his job in Calgary and that’s how we ended up on the farm,” says Kiyooka. “But he was a city person. He didn’t know how to farm. In fact, he didn’t know the front end of a horse from the back!”

After the war, Kiyooka knew he had to earn a living and made the practical decision to study education at the University of Alberta. After seven months of studying, he got a job teaching at a school in a small German-Canadian community in Eastern Alberta. Much of what he earned, he sent home to his parents.

Art came later, after his older brother, Roy, made the leap first. “My parents didn’t really encourage us to be artists,” says Harry. “But, when both my brother and I started earning a living from it, they thought it couldn’t be so bad.”

Ohe’s family, by contrast, was more supportive of her artistic ambitions. As a child growing up near Peers, Alta., (a hamlet northeast of Edson), she spent hours drawing and creating. She was 16 when she learned about the Alberta College of Art (now Alberta College of Art + Design) and announced to her parents she was going to art school.

“When I told them they smiled and said, ‘You must do what you are,'” reminisces Ohe. “I’ll always remember that. ‘Do what you are.'”

And she did. Ohe studied at ACA just like she said she would, and it was there that she found she had a natural talent for sculpting, rather than for painting or drawing. She worked with clay, then with cement, then with metal after the general manager of Dominion Bridge, a steel bridge-construction company, invited her to the site before working hours to learn to weld using Dominion’s scrap metal.

But, in the early 1960s in Calgary, to excel further at sculpture meant leaving the city. After graduating from ACA in painting (there was no sculpture department at the time, she says), Ohe continued to learn from the best, locally and internationally. While studying in Montreal, she learned from Arthur Lismer, one of the Group of Seven. From there, Marion Nicoll, one of Alberta’s first abstract painters, and Archie Key, director of the Calgary Allied Arts Centre until 1964, arranged for her to study sculpture at the Sculpture Center in New York; she spent three years taking post-graduate studies there. A number of years later, the assistant director at the Sculpture Center, who by then had become dean of sculpture for Columbia University in New York, invited Ohe to join him for a summer working in a foundry in Verona, Italy.

All the encouragement and support resulted in the creation of countless kinetic sculptures that are landmarks in Calgary – think of Zipper at the University of Calgary that students still spin before exams for good luck, or Nimmons Cairn in Nimmons Park in Bankview. There have also been numerous private and public commissions across Alberta and sculpture, print and painting exhibitions around the world.

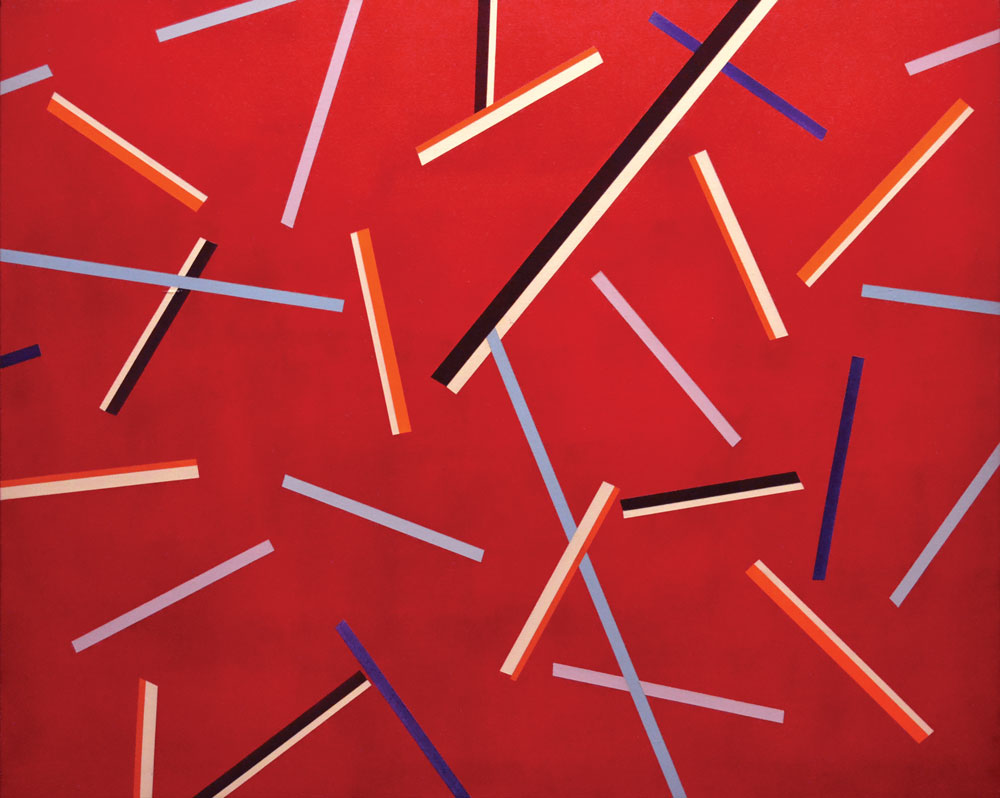

While Ohe studied to improve her craft, Kiyooka studied fine art in an academic setting. He has four advanced degrees from universities in Canada and the United States, and, from 1958 to 1961, he had a studio in Anticoli Corrado, a small mountain village outside Rome, assisted by a Canada Council grant. His abstract paintings have been showcased nationally and internationally, but one has to search a little harder to find out where. When asked, Kiyooka sidesteps the question, directing the conversation to anything but his achievements. Search for his work yourself and you’ll wade through a plethora of information on his brother, Roy Kiyooka, a more well-known and more extroverted artist, before finding much on Harry.

“Harry didn’t seek the limelight,” says Deborah Herringer Kiss, director of the Herringer Kiss Gallery of Contemporary Art, who has known the couple for more than 15 years. “He didn’t care about having big shows or trying to get into museums. He didn’t care about any of that. He made it work by quietly, constantly creating art.”

A couple years shy of 90, Kiyooka is still a prolific painter. Inside his and Ohe’s home, his paintings hang alongside the “greats.” Other paintings line the walls of his studio, and he still works on several huge canvases. More paintings are stored behind couches and under beds, and there’s a dedicated storage room packed with filing cabinets, filled with his paintings.

When asked how many paintings are filed away in the storage room alone, Kiyooka lets out a deep laugh. “I can’t even begin to tell you how many are in here,” he says.

Calgarians connected to the art scene know Kiyooka and Ohe as respected and recognized artists who probably could have succeeded anywhere. Instead of pursuing careers in the art hubs of the world, however, they chose Calgary. In doing so, the duo has proven that the best can stay in Alberta and give back to the community, inspiring a range of well-known art enthusiasts in the city along the way.

Herringer Kiss understands what this means for Calgary. “Being a successful artist used to mean leaving for Toronto or New York,” she says. “Katie and Harry are showing young artists that just isn’t the case anymore. You can stay in Alberta and still have a successful career as an artist. And they are truly living legends – I was awestruck and tongue-tied when I met them in person for the first time.”

Kiyooka, ever-practical and unpretentious, credits the University of Calgary offering him a job for his return to Alberta in 1961, while Ohe says keeping Calgary her home base honours her beginnings. “I had tremendous support here,” says Ohe. “I attribute all of that to the Alberta College of Art – they did everything for me.”

Ohe, still a part-time instructor at ACAD, has been teaching art since 1959 and has been with ACAD since 1970. As a teacher, she has promoted the creativity of a diverse range of students. While teaching at the Calgary Allied Arts Centre, she also worked and lived out of the Hart family’s carriage house – that’s the Hart family of wrestling fame. Ohe taught art to the “Hitman” himself, Bret Hart, the eighth child of wrestling patriarch Stu Hart.

Now retired from professional wrestling, Bret Hart remembers meeting Ohe when he was seven or eight. He’d watch her weld in the carriage house, his eyes burning after staring at the bright white light as she worked. He’d watch her lift heavy metal and transform it into something that had a life of its own. Mostly, he remembers learning from her. Every Friday night, Hart would go to the wrestling matches with his dad to hand out programs. He’d get home around midnight, still buzzing with the energy from the crowd, but he’d still be up the next morning for an art class with Ohe.

“Katie made me feel like I had that ability to become an artist,” says Hart, who still loves drawing and cartooning. “I always wished she could have been one of my schoolteachers. She gave me that confidence and helped me get to the next step.”

Local artist Rhonda Barber was another student of Ohe’s, this time at ACAD in 2004. Barber remembers making sure she took a sculpting class with Ohe. She’d seen the pieces that moved silently and fluidly and heard the rumours (teachers and students, alike, referred to her as the God of Sculpture). Like Hart, Barber can list endless influences Ohe had on her work, but it was Ohe’s mentorship that shaped her most.

“I think in art school, you wonder if you’re really an artist,” says Barber. “But Katie made me feel connected and supported. She helped me realize I can be an artist.”

Kiyooka, meanwhile, built his teaching career at the U of C. Alexandra Haeseker, an artist who has shown work around the world, took her first drawing class there from Kiyooka (she says she also studied sculpture under Ohe at an early age). Kiyooka was an academic trailblazer for fine art: Haeseker remembers him inviting prominent foreign artists to visit and teach for a semester or more, and his goal, Haeseker says, was to establish an MFA program at the university.

“He worked hard to make the university better for students interested in fine art,” says Haeseker, who graduated with a master of art degree with a fine art major, and who had Kiyooka as her graduate thesis advisor.

Through their teaching and their dedication to their work, Ohe and Kiyooka have influenced generations of artists. Part of their legacy is the people who have known them: Kiyooka and Ohe have helped shape world-class creators including Evan Penny, Christian Eckart and Chris Cran. And their enthusiasm shaped generations of art-appreciators among those students who didn’t go on to become professional artists.

“They have a real conscious belief that art is their responsibility,” says Haeseker. “That is very catching!”

Over the years, Ohe and Kiyooka have also taken on responsibilities at various art institutions. Now a professor emeritus of art at the U of C, Kiyooka was a founding member of the Calgary Contemporary Arts Society, president of the Alberta Society of Artists and the founder of the Triangle Gallery of Visual Arts (now part of Contemporary Calgary).

“They’re always there, always working really hard to produce new work and always supporting anything that promotes art,” says Haeseker. “Whenever you look back at art in Calgary over the last 50 years, Katie and Harry have always been present. And a lot of their pieces are now like old friends.”

Their dedication and sense of responsibility to art isn’t slowing down. Having actively fought for Calgary to get its own civic art gallery, the couple is now in the process of turning their home and studios into the Kiyooka Ohe Art Centre (KOAC), a charitable society and gallery overseen by a board of directors. On Sept. 11, 2015, Kiyooka and Ohe signed the official document turning the title of their home over to the KOAC, although they will continue to live there.

Incorporated in 2007 and still in the fundraising phase, the KOAC will be a tangible reminder of Kiyooka and Ohe’s artistic and teaching legacies when complete. It will become a place for artists to study and do residencies. More than 2,000 art books will become the research library. The land surrounding the buildings will be transformed into the area’s only sculpture park. The final phase of the project is the construction of the pavilion – the gallery portion of the art centre – that will house a collection of contemporary artwork for anyone to come and admire.

“The KOAC is interesting because it’s showing the history of Alberta art as it links to international contemporary art,” says Herringer Kiss. “They’re teaching us the history of contemporary art in Calgary, and that will make us all richer.” That teaching comes in many forms, over and above the classroom instruction hours that Ohe still puts in, and their continued mentorship of other artists, to include the examples that they set in their own lives and in the work they continue to make.

Sitting on a shelf in Kiyooka and Ohe’s home is a white box, small enough to hold in your hands. Haloed with sun by the room’s skylight, this sculpture, The Family Box, is one of Ohe’s earlier works, unique among others that stand metres tall. Upon first glance, it’s simply a beautifully designed box. But with a few quick twists and turns, the piece unfolds out into a square and becomes four people, inseparable.

Like the art centre being created in Springbank, and the careers of its founders, The Family Box doesn’t beg to be noticed. It would fly completely under the radar if it wasn’t pointed out. But it’s a perfect symbol of something Kiyooka and Ohe have long known, and have spent decades helping the rest of the province understand, too. It’s that we are all inextricably connected to art, and that art is a part of all of us, quietly asking us to interact with it.

And that is exactly the message the KOAC will also quietly send when it is completed.

Artwork by Ohe and Kiyooka you might recognize