In the summer of 1992, Bret “the Hitman” Hart, in his trademark pink leotard and shades, stood before 80,000 wrestling fans in London’s Wembley Stadium for what he considers the fight of his career: a main event against his brother-in-law, the “British Bulldog,” Davey Boy Smith. They were two athletes at the peak of their physiques, outmaneuvering one another for 30 minutes, each suplexing his opponent’s 100-plus kilogram frame with the lightness of a load of laundry.

In a quiet room of the Sheldon M. Chumir Clinic in downtown Calgary, 24 years later, the Hitman is struggling to squeeze a steel dynamometer with his right hand. Chest puffed, eyes closed, lips and jaw clenched, he grips the force measurement tool until Kathy McDonald, a zen-like physiotherapist, tells him to stop. “Like a toddler,” he grumbles after exhaling. McDonald writes “6 kg” in her chart and asks him to do it again.

Hart wasn’t just Canada’s most famous strongman; he was, for some years, the world’s – an icon, a god. As the World Wrestling Federation‘s five-time World Heavyweight Champ, he could enter a school in India with title belt slung over his shoulder and get swarmed by adoring kids. They were but a few hundred of the tens of millions of people watching him weekly.

The last two decades of his storied life, however, are less lustrous: floundering fame, family tragedies, a career-ending concussion, bitter divorces, sibling squabbling and a spate of health problems, including prostate cancer, which he made public this year after treating it silently for months. The most debilitating recent event, ironically, was wrist surgery that was supposed to resolve issues from decades of injuries. He had two pins inserted into each wrist, but it has left him with massive swelling, unspeakable pain and possible nerve damage in both hands, especially the right. “You add up the knee surgery, the prostate cancer surgery and the two hernia operations all together and it wouldn’t hurt as much,” he says. “Might as well put my hand in a bear trap, dip it in oil and light it on fire.”

Hart releases his grip – eight kg – and repeats the exercise.

At the moment, the “Excellence of Execution” struggles to button his pants and push elevator buttons with his index fingers. At autograph signings, he says, some fans look at him like he’s “mentally handicapped” or “illiterate” while he scrawls his hardly legible name. But he’s determined to beat this and the cancer into submission like they’re Stone Cold Steve Austin at Wrestlemania XIII. He knows he will because he’s already won the real fight of his life: In 2002, Hart, riding his bike along the Bow River, crashed and suffered a stroke. He was in a wheelchair for three months and had no sense of whether he’d walk properly, let alone fight, again. He has, of course, since done both.

With a gust of breath, Hart lets the dynamometer drop with a clang. “That’s everything I got.”

“Ten,” says McDonald, marking the improvement. “That’s the competitive nature in you, to get higher and higher.”

After the exercises, McDonald straps a velcro splint over Hart’s right hand and forearm and instructs him to wear it for 20 minutes before driving home. He waits it out in the on-site caf with a cream-soaked coffee and is occasionally interrupted by selfie-seeking fans. His curly grey hair is as long as it was when his posters adorned bedrooms and lockers, and Hart’s face, though jowly and worn, hasn’t lost its signature seriousness. His muscularity has softened, but even in blue jeans and a navy tee the Hitman is an unmistakable sight.

If cancer is a disease of aging, then Hart’s disposition is, ironically, a testament to his relatively strong health. “Relatively,” because at 59 he’s outlived dozens of cohorts who treated the job’s physical and mental abuse with prescription painkillers. According to a report on HBO’s Real Sports, in the early 2000s, some wrestlers popped as many as 100 pills a day; a 2004 follow-up flagged concerns over the high number of pro wrestlers who “died young” over the previous seven years (more than 60) citing drug overdoses, natural causes, car accidents, suicides “and everything in-between,” with the reporter adding “at least” 23 wrestlers around the world had died in the preceding three years alone. That includes 39-year-old Davey Boy Smith, whose fatal heart attack was attributed by an inquest to an enlarged heart, but some blamed it on steroids and human-growth hormones.

Hart didn’t always abstain from the lifestyle that has built a cult of death around the sport, washed away the glamour, stained it with grime. He documents it with brutal honesty in his 2007 autobiography, Hitman: My Real Life in the Cartoon World of Wrestling. “My release, my amnesia or maybe my anesthesia, was women,” wrote Hart, who was married to the mother of his four kids, Julie Hart, throughout his professional career. “Sex seemed like the lesser of all the sins that lay in wait for us.”

Today, he says it was more than choosing the lesser evil. Like his father, legendary trainer and Stampede Wrestling promoter Stu Hart, “I always had a strong will.” Bret’s dedication to self-improvement, to be, like his catch phrase, “the best there is, the best there was, and the best there ever will be” warded away many of the demons that led to self-destruction and financial ruin. “So many wrestlers are broke by the end of their careers. You can count the successful ones on one hand.”

As if in a scene scripted by pro-wrestling writers, the Hitman is suddenly interrupted by a haggard, fast-talking man in a dirty ball cap: “You wouldn’t happen to have a loonie for bus fare would you – hey, Bret, how you doing? You don’t remember me, do you?” Reading puzzlement in Hart’s expression, “J. J.” lifts his sleeve to show a small wrestling ring tattooed on his forearm. “I used to wrestle. When Dean was around,” he says, referring to Hart’s fifth oldest sibling, who died of kidney disease in 1990.

“That’s a long time,” says Hart. J. J. proceeds to blather about once weighing 220 lbs. and bench-pressing twice that. Throughout the encounter Hart is skeptical of the panhandler’s biography, but polite. “I hope you’re doing good.”

“I hope you’re doing good, too,” says J. J., nodding at Hart’s cast.

“Getting there.”

To fathom Hart’s psychology – his blunt honesty, constant need for self-improvement and remarkable pain tolerance – it is not simply enough to acknowledge that he’s a professional wrestler. Rather, one must understand what it was like growing up as a middle child in the historic Hart House.

Stu and Helen Hart had eight boys, all wrestlers, and four girls, all, at some point, wrestlers’ wives. It was in the basement of their Patterson Heights brick mansion that Stu, a traditional “shooter” style fighter, put the boys through martial arts-inspired moves that tested their pain points and bordered on abuse. The vents filled with their screams and those of grown men – footballers, Olympians, a who’s who of pro wrestling like the Iron Sheik and Jake “the Snake” Roberts – that forfeited their pride for a chance to get “stretched” in the Hart Dungeon. The emphasis on technique made the boys a different breed of wrestlers. They were old school compared to the veiny-armed, vaudevillian characters of the 1980s – big on personality, short on skill – and Bret Sergeant Hart, the third-youngest son, though he lacked charisma, possessed an expert sense of realism atop his handsome ’80s coolness at a time when it was most needed by the industry.

“Bret was a star,” writes David Shoemaker in The Squared Circle: Life, Death, and Professional Wrestling, “but certainly nobody would have predicted his future as a long-term heavyweight champion, as he was several inches too short and several degrees too plain to compare to the likes of Hulk Hogan or Randy Savage.” But in the early 1990s a steroid scandal and legal troubles rocked the World Wrestling Federation (renamed World Wrestling Entertainment in 2002, now just WWE) and president Vince McMahon went looking for a new star to counter the negativity. He found it in this natural looking “technician.”

Along with his contemporary, “the Heartbreak Kid” Shawn Michaels, Hart represented a shift in who wrestlers could be, how they could wrestle and what main-event matches could look like, says Dorothy Roberts (no relation to Jake the Snake), an Edmonton writer and wrestling expert. “In the 1980s, wrestling was muscle-bound, superhero-looking men just beating on each other without any athleticism,” she says. “The idea that someone who is not 6’5″ and 250 lbs. could be successful stems directly from Bret Hart. He inspired people who don’t look like giants and supermen.”

Standing a modest six feet tall, Hart upended the cartoonish era with submission moves like his Sharpshooter (a leg-lock inspired by his father), as well as a character gimmick that was, essentially, a slightly amplified version of himself. While wrestlers on the microphone spouted soliloquies about voodoo witch doctors or whatever, Hart talked – never yelled – about his family and Calgary roots in a way that blurred reality. Above all else, says Roberts, he was the ultimate storyteller with a masterful ability to combine moves in a way that logically built each match to a believable conclusion.

But for all his influence, Hart’s personality as a positive role model was becoming antiquated. Today, good-versus-evil storylines have been replaced with nuanced rivalries. The shift began in the late ’90s, when the WWF turned increasingly shocking and obscene, filled with dick jokes and sexual innuendo (Michaels even once implied on TV without warning that Hart had slept with popular wrestling valet Sunny). The Hitman’s real-life disappointment with the product became a storyline. He was one of wrestling’s last true good guys.

The reality-bending that Hart injected into wrestling would come back to bite him in November 1997 during a match forever known as the “Montreal Screwjob.” The Hitman, set to leave the WWF for Ted Turner’s now defunct competition, World Championship Wrestling, had one last match, in his home country, which he was led to believe would end in a draw. It instead ended with Michaels abruptly beating Hart with his own finishing move, a conspiracy hatched by him, the referee and Vince McMahon, whom Hart considered a father figure for both his mentorship and fearsomeness. “Looking back at it,” Hart says 19 years later, “the Screwjob was the only one real thing to ever happen in wrestling.”

Reality and wrestling collided tragically two years later, when his brother Owen fell 24 metres to his death while entering the ring from the rafters. The accident – which was not broadcast, with viewers instead only seeing the shocked commentators discussing efforts to save the wrestler – sent shock waves through the sport and tore a rift in the Hart family that has never fully healed.

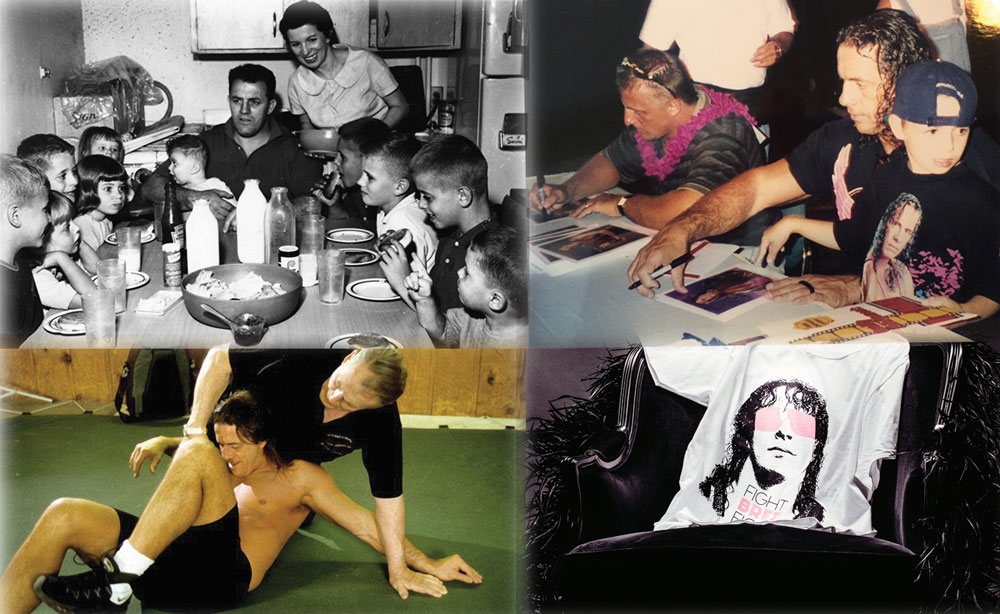

Clockwise from top left: Family photo at the Hart house, 1958; Hart (centre) with brother Owen and son Blade in 1997; “Fight Bret Fight” T-shirt from a merchandise fundraiser for cancer research; Bret wrestling with father Stu Hart.

The scene inside Hart’s Springbank Hill home vaguely resembles the historically designated Hart House, with brick accents on the outside and, on the inside, roaming cats and three generations of family – at least temporarily. His eldest, Jade, who is seven months pregnant with her second child, and her husband are living in the sprawling bungalow while their new home is built. While granddaughter Kyra chases her friend, Jade, who does brand management for Hart, helps tie her dad’s hair into a ponytail. His youngest, Blade, 26, who co-hosts Hart’s podcast The Sharpshooter Show with brother Dallas, stalks the kitchen in a T-shirt that reads “Fight Bret Fight” (a merchandise fundraiser for cancer research). And though the basement is a far stretch from Stu’s Dungeon, it is a formidable man cave, with an elaborate table hockey set-up. Hart, his sons and friends compete weekly in the “Western Canadian Table Hockey League,” vying for a slick title belt. “I’m still in there, and I’m working with seven fingers,” boasts Hart, who, unsurprisingly, plays as the fantasy Hitmen, a nod to Calgary’s Western Hockey League (WHL) team that he co-founded with Theo Fleury and Joe Sakic in 1994. (They have all since sold their shares.)

There’s a big happy family vibe at the new Hart House, but it’s far from Rockwellian. Bret was on the road and mostly absent for almost all their childhoods. Family life continued to be rocky for the first years of retirement, as he and Julie divorced and his second – and brief – marriage to a much younger Italian woman irritated the kids. Stephanie Washington-Hart, his wife of six years, is a year younger, but as a social worker, says Hart, she possesses a gentleness and considerateness that his adult children have taken a liking to. There is, however, less cohesion among the extended Hart family.

There was never a moment without sibling rivalries, and they weren’t always healthy. Hart’s book is rife with anecdotes of jealousy, lying, backstabbing and financial squabbling – as is sister Diana’s autobiography, Under the Mat: Inside Wrestling’s Greatest Family; brother Bruce’s Straight from the Hart; Owen’s widow Martha Hart’s, Broken Harts: The Life and Death of Owen Hart (co-written with Eric Francis); Marsha Erb’s authorized biography of the family patriarch, Stu Hart: Lord of the Ring; not to mention ex-wife Julie’s Hart Strings: My Life With Bret Hart and the Hart Family. Many of them paint the golden child, Bret, as egotistical, short-fused and controlling.

Things got especially sordid after Owen’s death. His widow, Martha, ex-communicated her in-laws, and the family became divided over whether to pursue legal recourse and disown the industry entirely. Helen’s death in 2001 and Stu’s in 2003 was heartbreaking, says Keith Hart, 65, the third-oldest child, but losing their baby brother was a traumatic experience from which they have not recovered. “Owen was so loved,” says Keith. “If there was anyone in the family who bridged all the tension, it was Owen.”

Having retired from wrestling early for a life out of the spotlight in firefighting and education, Keith has taken on a peacemaker role. Living in the shadows of Stu and Stampede Wrestling bred “a bunch of alpha males,” he says. “There was so much pressure to achieve and vie for the top billing, to be the number one son in my dad’s eye. And the business itself, just the temptations in it, it’s almost biblical. There were all sorts of things that could sidetrack you, including hubris. Soon as you think you’re better than the next, somebody’s going to knock you down a peg.”

Bret also describes the dynamic with a wrestling metaphor: “It’s almost like they turn ‘heel’ and then, the next week, turn ‘babyface,'” he says about a few of his siblings, using the sport’s lingo for bad guys and good guys. His relationships with older brothers Bruce, 66, and Smith, 67, are particularly strained. Among the many reasons, Bret says they posed as him to sell forged autographs. Smith doesn’t deny it: “I can sign his signature better than he can.”

Smith and Bret rarely see each other, let alone speak, but late last year they bumped into each other in an elevator at the Prostate Cancer Centre. The brothers were fighting the same disease separately for months. They even shared oncologists. While Bret was preparing for surgery after learning he had irregular PSA levels, Smith’s cancer had spread to his hip bone and he required hormone therapy, bisphosphonate drugs and chemotherapy, which have sickening side effects. Bret says the quarrels with Smith have softened in recent years, but he wishes his eldest brother made better decisions with his life and health, schemed less and took more responsibility. (Smith infamously had to be forcibly removed from Hart House by police when it was sold in 2003.) “I don’t have a lot of pity for Smitty,” says Bret.

Keith hopes their illnesses will inspire the brothers to put the past behind. “When it comes to health you realize how thick blood is,” says Keith. “You don’t always have that spark and cause to come together and really pour your hearts out till you have something like that.” Smith, who does not have a prognosis, says he’ll spend his remaining time writing his autobiography and training his son Matt Hart to wrestle.

On a Friday evening in early April, the wrestling world has descended on Arlington, Texas, near Dallas-Fort Worth, for Wrestlemania 32, set to draw the biggest crowd in its history, with 101,763 fans at AT&T Stadium. Hart is usually one of them, but on this night he’s skipping the industry’s biggest event to spend time with family and friends in Calgary over dinner at Pulcinella followed by a Calgary Hitmen game.

At dinner he sits with Washington-Hart, a strikingly beautiful African American from San Francisco, whom he met at an autograph signing in 2008. She is a bona fide “smark” – one who appreciates the sport on a higher level – though she downplays it because, admittedly, it weirds people out that Hart married a fan. “You still have to get to know the person,” she says. “So when people ask what’s it like being married to Batman, I say, ‘I don’t know. I married Bruce Wayne.'”

“It’s not like I’m walking around in pink leotards,” he adds.

“Or putting me in a Sharpshooter,” she says.

The couple started dating just after Hart’s second divorce, a time when he’d hit rock bottom. “I kind of went into a shell,” he says, slowly forking calamari with his dominant, and difficult, right hand. “Especially after I got hurt, my concussion, my stroke – I became a sympathetic character.”

Of all his accomplishments – the many championship belts, the millions of fans, the indelible mark he left on wrestling – Bret Hart considers overcoming a stroke his greatest achievement. His only goal when he arrived at the Foothills Medical Centre in 2002 was to walk and speak normally, but at the back of his mind he wanted nothing more than to feel again the stadium spotlight on his neck, the rumble of his theme music in his boots.

“Bret arrived in a wheelchair,” recalls Brenda Brown-Hall, a slight physiotherapist standing five-foot-nothing. “The first time I picked up his leg I thought, ‘Oh shit, this one’s going to be heavy on me.'” Hart was incredibly motivated and driven, she recalls. “We’d be in the stairwell, going up the stairs, backwards, sideways, two at a time – working like a madman to get his power back.”

After about three months, he was walking again, and in two years he’d almost fully recovered. Hart became a role model to other stroke patients, visiting and befriending them, giving them motivational talks in their darkest hours. Hart calls Brown-Hall his “hero” and “saviour,” and he accepted her invitation to speak at an Allied Health open house – an appearance that was well received. He’s also leveraging his celebrity for cancer research and awareness, raising funds through merchandise sales and evangelizing regular prostate screenings. The Calgary Prostate Cancer Centre saw a spike in new screenings following the announcement of his successful prostate surgery in February. “Bret is such a positive role model and a good Albertan,” says Brown-Hall, who fractured her wrist in 2014 and suffered a further injury that led her into hand therapy around the time Bret was fighting his prostate cancer battle. The two supported each other, texting encouraging words to the other when they were blue.

Prostate cancer scared Hart, especially when he learned about its sexual side effects (“I felt like a cat signing up to get neutered”), but subsequent checkups suggest the surgery was successful. (That said, it could be a couple years before he can say he’s “cancer-free.”) It’s the searing pain in his wrists and immobile fingers that is most defeating. The injury stemmed from a 1981 match in which he improperly fell and broke his scaphoid bone in three. Hart tolerated the pain for 34 years until it was too unbearable and the bones were too degenerated. Last fall he got a four-corner fusion, which was supposed to reduce pain and preserve wrist motion, but he says it has only made things worse. “I may never do artistic things again,” says Hart, a talented cartoonist who learned to draw as a teen from artist Katie Ohe. “It makes me angry.”

The surgeries have resulted in his longest absence from training since the stroke, making him feel like a “big lazy cat” on most days. He’s keen to return to riding his bike, yoga with Washington-Hart and doing muscle and cardio workouts with his personal trainer, competitive bodybuilder Roy Hertz. “The gym does some amazing things for rejuvenating the nerves, but it’s going to be a challenge,” Hertz says, adding Hart has progressed faster than he anticipated.

Remnants of Hart’s hemiparetic stroke are faintly visible on his body’s left side. The hand moves slower and, as he climbs to his seat in the Stampede Corral, there’s a slight limp in his left leg. He’s followed by Washington-Hart and two friends that he invited to the game, a playoff match between the Hitmen and the Red Deer Rebels. On the way in, he was irked to see that the framed photo of his father, who held special Stampede Wrestling events in the 66-year-old stadium, had been taken down, so his surliness is noticeable even as fans shout “Hitman!” and “Mr. Hart!”

In recent years Hart has become known as wrestling’s crotchety old man, often taking to his podcast to rip apart industry practices, its apparent mistreatment of wrestlers and its generally poor quality (another reason he’s skipping Wrestlemania). The Montreal Screwjob, Owen’s death and a concussive kick to the head that forced his retirement in 2000 have no doubt blighted his opinions. When it came time to reflect on it all in Hitman, he neither avoided tawdry details nor his opinions of his counterparts. But instead of bringing closure to his athletic life, as he hoped, it opened another unwritten chapter, one in which his reputation went from being one of the industry’s greatest professionals to one of the sourest lemons.

“His ego is out of control,” hall-of-famer and former WWF world heavyweight champion Kevin Nash, a.k.a. Diesel, said in an interview for the independent online documentary Burying the Hitman. “I always felt Bret cared a little bit more about Bret than anything else,” Scott Hall, a.k.a. Razor Ramon, said in a 2002 interview featured in the same documentary. “Malicious” was Hulk Hogan’s description of how Hart depicted some of his fellow wrestlers in his cartoons.

Though Hart stands by the book because he intended to write it as he felt in the moment, he regrets how it sometimes comes across. “I wrote my book, said everything I wanted to say, how I wanted to say it, then I realized everyone thinks I’m bitter, angry.” Unsurprisingly, Hart saved his harshest words for Vince McMahon, whom he describes as a “son-of-a-bitch” on page two.

In truth, by the time it was published in 2007, they were reconciling and Hart had already been inducted into the WWE’s Hall of Fame. Not all family members were pleased with his acceptance of the honour – according to Bret, Martha Hart continues to block the WWE from doing the same for Owen. But there is nothing more important to Hitman than his own legacy. “By carrying around a lot of hard feelings,” he says, “I realized there’s a lot to be said for forgiveness.” He stops short of extending forgiveness to his feuding siblings, however. “I have no reason to yet.”

Hart with niece Natalie Neidhart, a.k.a. WWE wreslter “Natalya.”

Six years ago, in a segment few could have imagined, Hart returned to the WWE to face McMahon. The cleverly scripted feud saw the president shake Hart’s hand – then kick him in the crotch. Crotch kicks were a pet peeve of Stu’s, and Hart is unsure whether his late father would approve of him doing business with McMahon at all. But wrestling is Bret Hart’s life, all he’s ever known. So, despite his pointed criticisms and disillusionment, he continues to crop up in WWE, sometimes accompanying his niece Natalie Neidhart to the ring.

The family’s unlikely third-generation torchbearer is part of a wave of female wrestlers elevating the women’s division from a titillating sideshow to near-equal status, and the Hitman, though unable to do much in “Nattie’s” corner due to his disabilities, is just happy to be a part of it. He needs to maintain a connection to that world, even if it’s standing in his niece’s corner, or forgiving the man he once called a “son-of-a-bitch.”

“Your life is out there. The friends you know, all the people you know,” says Hart. “It means the world to me that I’ll never be forgotten.”

[Correction: A previous version of this story called Hart’s granddaughter Vira. The story has been updated with her correct name, Kyra]