Guy Weadick shows up at your home asking if you want to be a part of his outdoor rodeo show. You’re skeptical. You’ve been thrown in jail multiple times for leaving your reserve without a pass, even though the reserve you now call home is a fraction of the space that used to be available to you for hunting, fishing and trapping. But you realize Weadick is serious. He wants you to parade through downtown Calgary in the very outfits you’ve been thrown in jail for wearing outside of your reserve. He wants you to dance and sing in your language, which you’ve only been able to do in private or face punishment, all for the benefit of his Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth.

And he and his partners will be the ones to jump through the bureaucratic hoops — the ones to get a short-term pass on the Indian Act, essentially — to make it happen. What would you have done?

“Well, of course [First Nations people] came,” says Violet Meguinis, an intergenerational teepee owner and Calgary Stampede First Nations events committee member. She and her family have owned a teepee at Stampede since Weadick himself came asking the Treaty 7 First Nations people to participate in Stampede. “He had the cowboys on board, but he knew that to make this the experience he wanted, he had to have the Indigenous people involved.”

However, getting the Indigenous people involved was not an easy task. At that time, First Nations communities were strictly governed by the Indian Act, a federal legislation that concerned the interaction between Indigenous people and the Canadian government. The Indian Act stopped First Nations people from practicing their traditional ceremonies and cultural heritages. Those who didn’t follow the rules faced penalties including hard labour and even jail time.

Such harsh punishments nearly halted Indigenous participation in the Stampede altogether. But Weadick was adamant on having them as a permanent staple of his show.

Weadick romanticized the cowboy lifestyle. “Visit Alberta before the golden opportunities, picturesque riders and Indians are gone,” reads one poster from 1908 when Weadick was trying to rally public interest for his rodeo. He knew he couldn’t have his wild west exhibition without the cowboys and the “Indians.” So, he partnered with prominent local politicians, including Senator James Lougheed and Richard Bedford Bennett, and they lobbied the Canadian government, with much difficulty, to get a temporary exemption to the restrictions of the Indian Act and he won over the First Nations people themselves.

‘“When you’re suppressed and you have to hide yourself, your identity, all of your ceremonies and your outfits, and if you can come and do it publicly, of course they came,” says Meguinis. “I choose to look at Calgary Stampede in that light.”

The relationship between the teepee owners and the Calgary Stampede is unparalleled. The first days of Stampede took place at a time when there was very little interaction between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, with First Nations tribes restricted to reserves. But at the Stampede, they were forced to interact.

What’s in a Name?

The old Indian Village embodied the unlikely relationship between Weadick, the Stampede and the teepee owners and the name was indicative of the language of its time.

The legislation created during that era referred to Indigenous people as Indians: the Indian Act, the Department of Indian Affairs, Indian Agents. Though some of the legislation still uses that language, “Indian” isn’t an accurate label for Indigenous people in Canada and, as such, is being phased out of use by most Canadians. “It’s not our word,” says Meguinis. “It was a word placed on us by the colonialist people. [Christopher Columbus] came across, and got lost, and called us Indians.”

When Indian is used to describe a person who is from India, then it is being used correctly. But when the word is used to describe a person of Indigenous ancestry, it takes on a different meaning and connotation. Then, it’s a term of colonial prejudice and racism toward First Nations people.

Rather than perpetuate the prejudices of the past, Meguinis hopes to use the Stampede as a platform to showcase authentic Indigenous culture. “We’re not just beads and feathers,” she says. “We have thriving communities. We truly believe in our sovereign right to determine what we want.”

Sovereignty is what drives Indigenous communities — it’s the justice they seek for a life and a land that was taken from them. The name change is a representation of that sovereignty in action and the decision to rename the Stampede’s Indian Village is one step closer for Indigenous communities to redefine who they are and where they’ve come from through their own lens.

Elbow River Camp

The new name, Elbow River Camp, was officially unveiled last July, but change had been percolating since 2016.

The old Indian Village was located on the south side of the Stampede grounds along 25th Avenue S.E., but the inconspicuous location caused the teepee owners to feel as if they weren’t really part of Stampede. The area was also prone to flooding. The camp moved to Enmax Park on the east side of the Stampede grounds across the Elbow River in 2016, and the Indigenous participants felt that the new location was even more reason for a new name.

“In the past, the name had been kept to honour the relationship with Calgary Stampede and Guy Weadick,” says Shannon Murray, Indigenous programming manager with the Calgary Stampede. “Many of the teepee owners would say the name ‘Indian Village’ is that connection to our past and our long relationship, but the context is changing.”

In 1912, Indigenous people were less than second-class citizens. They had no voting rights, couldn’t leave the reserve unless given permission and were banned from practicing their culture. When Weadick was insistent on having them in his event, they attended and they didn’t ask for more.

Today, many First Nations people sit on internal committees of the Stampede and are increasingly vocal and active in the organization. After re-examining the out-of-date name, it was decided unanimously that Indian Village was no longer acceptable.

Elbow River Camp was a natural selection for both the Indigenous participants and their Stampede counterparts, because the name held historical significance for the teepee owners. Before contact with settlers, many of the groups that now make up the Treaty 7 First Nations didn’t speak each other’s language, so they communicated through sign language. “We would communicate the sign for, ‘where are you going?’” says Meguinis. “The person would point to their elbow and we knew right away that was the Elbow River and they were going to Fort Calgary.

“This was our territory and this is where we interacted with each other,” she says. “This is a significant validation that Indigenous people were here long before contact.”

Moving Forward

Although it was the teepee owners who initiated the idea of changing the name, Murray says Stampede was receptive and listened to their Indigenous partners. “I keep using the word unique but there’s really not another way to describe the relationship the organization has had with these families from Treaty 7,” says Murray. “I know for the Stampede, this is just the next step in being a good partner and supporting the teepee owners.”

Now that the name has changed to appropriately represent Treaty 7 Nations, the teepee owners can focus on what’s truly important to them — educating others about Indigenous culture. “[The previous name had] always been a little hiccup,” Meguinis says. “But it’s done now and we can move forward and do the things we were doing before — building awareness and relationships, taking down misconceptions and empowering the youth.”

The Five Nations of Treaty 7

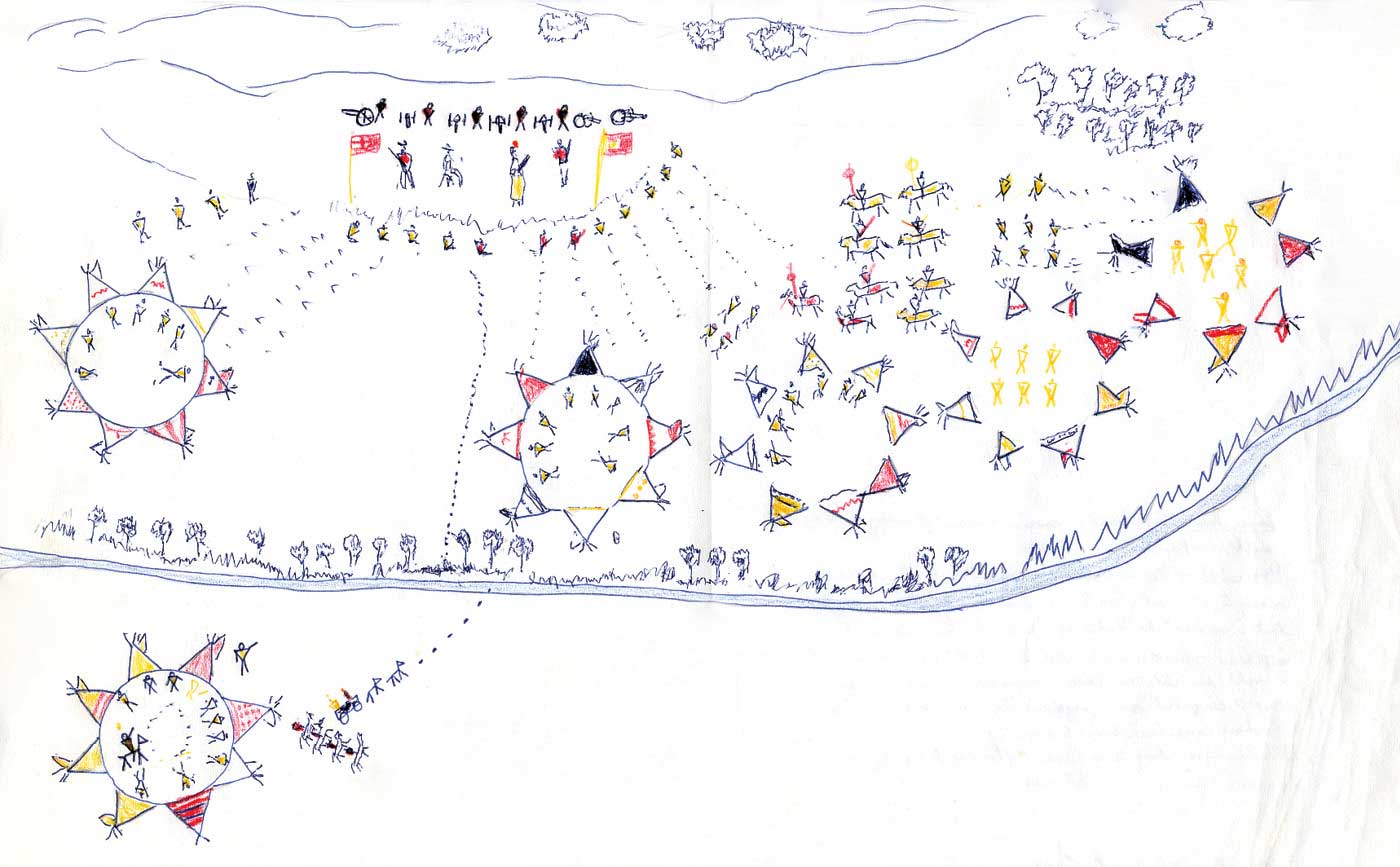

Each July, Treaty 7 First Nations gather at Elbow River Camp for the Calgary Stampede. Families set up teepees and camp on the grounds for the whole week, educating, teaching and demonstrating their traditional ways for guests. Here are some facts about each nation.

Kainai

One of three nations in the Blackfoot Confederacy, the Kainai, also called the Blood Tribe, has 12,800 members and occupy approximately 1,424 square kilometres. The Kainai reserve is home to Red Crow Community College, the first tribal college in Canada. The Blood Tribe keep their members and others up to date on local news with the magazine, bloodtribe.org/tsinikssini.

Nakoda (Stoney)

Nakoda (also known as Stoney) reserve is made up of three nations: Bearspaw Nakoda Nation, Chiniki Nakoda Nation and Wesley Nakoda Nation. Nakoda means “people” or “human.” The name “stoney” was placed on them by white settlers who observed how they cooked meals over fire-heated rocks, however, the Nakoda nations are moving away from this name, because it doesn’t properly represent them.

Piikani

Piikani is another of the three nations in the Blackfoot Confederacy. Members of the Piikani Nation were the first in Alberta to demand voting rights in provincial elections. They also acquired a large land mass because of adopting the rifle and horse in the 1700s. Today, the nation is 3,600 members strong.

Siksika

Siksika is also part of the Blackfoot Confederacy — its name literally means “Blackfoot” (sik (black) and ika (foot), with an s connector). Historical figures of the Siksika Nation include Chief Crowfoot and Chief Old Sun, who were revered warriors and leaders and also key participants in the signing of Treaty 7. The Siksika reserve is home to Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park, an interpretive centre about the history and rich culture of the Blackfoot nation.

Tsuut’ina

The Tsuut’ina are noted cattle ranchers, making them natural participants and competitors at the Calgary Stampede. If you still have some rodeoing left in you after Stampede, Tsuut’ina hosts its annual rodeo and powwow the last weekend in July on grounds five kms east of Bragg Creek.