20 Decisions That Shaped Calgary

A city becomes what it is by the accumulation of decisions made and the paths taken and not taken. To mark Avenue’s 20th anniversary, we take a look at 20 decisions, big and small, that have made Calgary what it is – a growing city, coming into its own, that we have had the honour and privilege of writing about for two decades.

Illustration by Steve McPhee

The Start of the Stampede Spirit

The first Calgary Stampede took place in 1912. Everyone in the city had that drilled into them with the 100th anniversary celebrated in 2012. A lesser-known fact is that the Stampede did not acquire its true personality and stamp Calgary with its cowboy culture until 1923.

Guy Weadick, the New York State vaudevillian who brought the original Stampede to Calgary in 1912, was not invited back until 1919. In the years following, his only Calgary gig was a fancy roping act with his wife, Florence, during two Calgary spring horse sales. Only in 1923 did Calgary Exhibition and Stampede manager Ernie Richardson propose that Weadick’s rodeo and the city’s exhibition be wed. The couple began the marriage under the name “Calgary Exhibition, Stampede and Buffalo Barbecue.”

Richardson’s annual exhibition had been losing money since the First World War due to an agricultural depression. In desperation, he signed Weadick to a six-month contract worth $5,000, as much as Calgary’s mayor made.

Weadick proceeded to weave his magic and set out to involve the whole city. To add an international veneer, he wooed celebrities to add their names to the show. Hollywood’s first power couple, Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks, as well as the Prince of Wales donated rodeo prizes.

But Weadick’s nearly mystical persuasiveness sparkled most brightly in his ability to convince Calgary’s business community to not only dress up their stores with slabs and hitching posts but dress themselves in cowboy hats, jeans and western boots. This was the same community that had not wanted Weadick’s first Stampede in 1912 because it was seen as cheap nostalgia for a bygone age. Getting those shopkeepers to don cowboy hats was like talking the people of Winnipeg into dressing up as buffalo hunters or Chicagoans as meat-packers.

Calgary’s 1912 Stampede rodeo had been a ramshackle affair without chutes or night lighting. Weadick put on a much slicker show in 1923 and added a brand-new event that was not just new to Calgary but to the world: chuckwagon racing. Teams of heavy horses would pull loaded chuckwagons around the racetrack. The winner was not the first to cross the finish line but the first to finish and then get a fire going in his stove.

Eye-witness reports called the first chucks chaotic, but, in that chaos of stoves spilling, rigs clashing and dray horses lumbering, the public saw something they liked, and Stampede chuckwagon racing has been famous ever after.

In fact, most everything Weadick tacked onto the Calgary Stampede in 1923 stuck. He was welcomed back year after year because his show had hauled Richardson’s Calgary Exhibition and Stampede securely into the black.

All of this is why Calgarians still dress western every July; why we scarf down free pancakes and attempt to square dance in painful boots; why outriders shoot poles and a fake stove into chuckwagons pulled by racing thoroughbreds for the “half mile of hell” – and why we all watch with our hearts in our throats. Guy Weadick is why. -Fred Stenson

Taking Ourselves Lightly

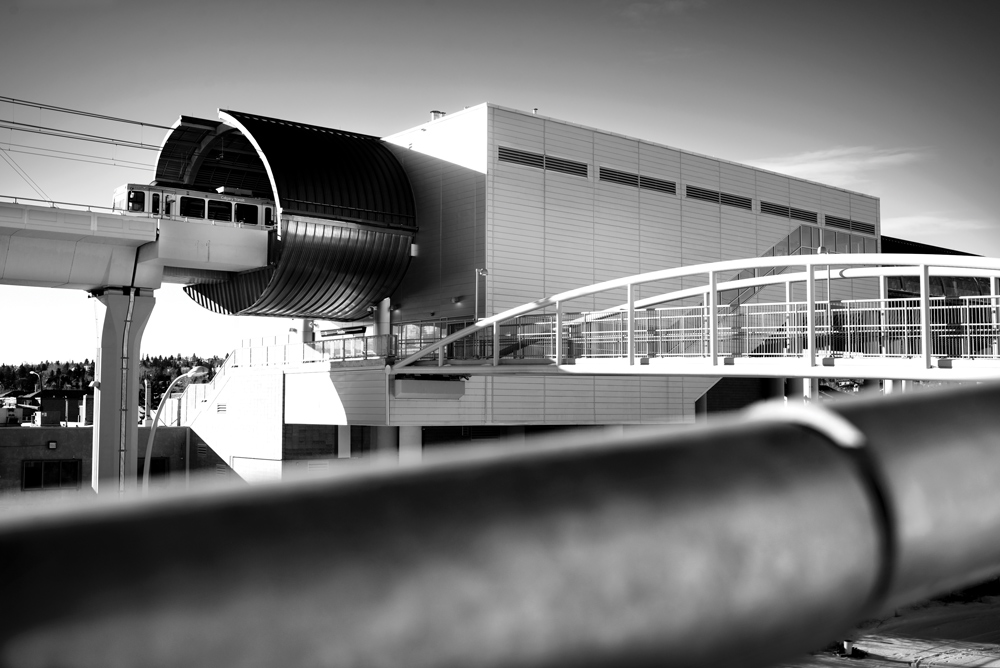

photograph by jared sych

The Sunalta CTrain Station, opened in 2012, was the first station in the west LRT line expansion.

Sometimes in politics the most momentous decisions are made far from the seat of power, in a series of choices so haphazard, it can almost seem accidental.

Such was the case with the most important transportation decision the City of Calgary has made in the last half-century: the choice of an LRT as the backbone of its mass transit system.

Today, as cities across the continent from Kitchener-Waterloo to Denver race to lay light-rail track, Calgary is far ahead in the game. The CTrain is the second-busiest light-rail transit network in North America, an efficient and (nearly) city-wide system that moves 260,000 passengers per day and was recently named by the Transportation Association of Canada one of the “Ten Triumphs of Canadian Transportation,” alongside more celebrated feats like the building of the transcontinental railway.

The choice of an LRT network, however, was far from inevitable. Indeed, it seems unlikely, even in retrospect. A major 1967 study for the City of Calgary recommended a single heavy-rail metro line, running at least partially underground, to link downtown to the southern suburbs. As a stopgap, Calgary Transit had introduced “Blue Arrow” express buses, and there was some advocacy at City Hall in favour of the lower-cost option of expanding this bus network. There was even talk of a monorail.

But then, in 1969, a City transportation official named Bill Kuyt visited Frankfurt, Germany, to look at its brand-new Stadtbahn. Here was a train running on lighter-gauge track, splitting the difference in cost and efficiency between streetcars and heavy-rail subways. Frankfurt’s Stadtbahn was among the world’s first modern LRT networks, and it didn’t even go by that name yet. “City rail” – the literal translation of the German term – was originally recommended for proposed North American trains; the term “light rail” only came into use in 1972.

In any case, Kuyt was impressed with what he saw. Advocates in Edmonton were also enthusiastic, and the provincial government handed them $45 million each to invest in new LRT networks. An LRT network became part of the City of Calgary’s plan in 1975. It was approved in 1977, and the first CTrain line from 8th Street downtown to Anderson station – following the original proposed heavy-rail metro route – opened in 1981.

The choice of an LRT proved especially crucial when it came time to expand the network. As cities like Toronto are learning, the debate over where and when to make costly investments in new subway lines can drone on for years. Cheaper light rail has been comparatively nimble: Calgary added new lines to the northeast in 1985 and northwest in 1987 (in time for the 1988 Winter Olympics) and to the west in 2012, and these lines are being extended station by station, from the nine original stations to today’s 45. Calgary managed to fund all this growth over a period when Toronto added only a single partial line of five stations to its subway network.

Try to imagine Calgary without the CTrain. Try to imagine commuting in Calgary with a quarter of a million more people on the road every day. The city’s transport system would be a congested body without a backbone. Every Calgarian owes Bill Kuyt a hearty Danke schn for bringing the Stadtbahn to Calgary. It’s the main reason we stand tall as a transit city. -Chris Turner

Party Faithful

No one parties like a Calgarian. But the accessory that most defines us when we kick up our heels isn’t the white Smithbilt hat or a pair of custom-made Buckaroos from Alberta Boot Co. It’s our chequebooks, which become much lighter at the end of July because of the generous donations to local charities that are the price of admission to Stampede’s highest-profile corporate hoedowns.

You can trace this potent loosening of our purse strings to a commitment made in 1993 by the founders of FirstEnergy Capital – Jim Davidson, Murray Edwards, Rick Grafton and W. Brett Wilson – to make philanthropy part of their corporate DNA, returning 2.5 per cent of their company’s yearly gross profits to the community ($35 million to date).

How then to make a real return on Western hospitality? Beginning with FirstRodeo in 1996, which evolved into FirstRowdy in 2004, FirstEnergy’s Stampede-related shindigs have generated $3 million for 50 charities. While FirstEnergy wasn’t the first local company to host parties that supported charities, arguably they made it bigger, splashier and more fun to have a charity event.

“Giving to get on the guest list” became synonymous with “doing smart business” and spread from the oil patch throughout corporate Calgary, from the banks and the builders to the microbreweries.

All of this means that, for CEOs, politicians and community leaders, Calgary’s most pressing social dilemma is not what to wear, but how many zeroes will provide optimal giddy-up. -Shelley Youngblut

Dining Alfresco

For Calgary diners, it was the Dark Ages. Restaurants of the 1960s and 1970s were cozy, closeted, dimly lit rooms where dining was a hushed, private affair.

But Stuart Allan, a publican recently arrived from the United Kingdom, wanted to eat outside. So he asked the Alberta Liquor Control Board (then ALCB, now AGLC) if he could open a patio with liquor service outside his new Buzzards Wine Bar. It seemed a simple request.

But the question had never been asked before. The ALCB debated. Only 14 years earlier, “ladies and escorts” had to drink in separate areas from tables of men. And it had been even less time since drinking establishments were even allowed to have windows. An ambiguous answer came back, “But we only have three months of summer.” Allan replied, “Then we’ll have three months of patios.”

The decision opened the cobwebbed gates of the ALCB. And so people ate – and drank – outside, adding colour and life to the streetscape. And the sky did not fall.

Other forward-thinking decisions followed. Soon, restaurant and pub owners could use chairs that had no upholstery, patrons could carry their own drink from one table to another and even stand while drinking, larger lounges could be built next to restaurants and, in the run-up to the Olympics, bar hours were extended. Then, in 1993, the Big Decision came – the privatization of liquor sales in Alberta, wresting booze from total government control.

A simple chain of events, all started by an expat Brit who wanted to have a burger and a beer outside. -John Gilchrist

Trail-Blazers

photograph supplied by qyd from wikimedia commons

Deerfoot Trail at the interchange with Beddington Trail, looking south.

The decision to name some of Calgary’s major arteries and landmarks for First Nations groups and members shows the city’s ongoing relation to the first peoples of the area, says Lorna Crowshoe, an issue strategist with research and planning at the City of Calgary and a member of the Blackfoot Confederacy from the Piikani First Nation.

“The naming was a great City decision because it will ensure we’ll continue to have a First Nations presence in Calgary. At the confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers was the establishment of our First Nations people, the Blackfoot people, and there is an archaeological history to support that that dates back 10,000 years.

“We tend to think that Calgary is 100 and some years old; it’s not. When you’re driving down Crowchild Trail or past Nose Hill Park, it is an opportunity to realize those names are part of our cultural memory. It’s not just First Nations history. If you are a Calgarian, it becomes your history, too.

“[Deerfoot] is named for a First Nations athlete and long-distance runner. Blackfoot is named after the trading route that was originally here. People have been using that route for centuries.

“As a Blackfoot person, it makes me really proud that our history is being incorporated into City discussions and that we’re being acknowledged as the first people of this territory.

“The street names are the first step, but we still have a long way to go. For example, the traditional name for Peigan is actually Piikani. The Peigan Nation, which I’m from, took on its traditional name, Piikani, at least 25 years ago. Peigan Trail is the anglicised version. The next step is to claim the traditional First Nations names for our city streets. That first decision has definitely allowed that to be more of a possibility today.” -as told to Meredith Bailey

Stalling Segregation

On Oct. 10, 1910, the Coloured People’s Protective Association of Calgary attracted 150 Black residents to a ball that lasted into the wee hours. Such merry-making was probably a welcome respite from the well-documented discrimination these early pioneers faced in their daily lives.

According to archived city council records and newspapers, members of racialized communities encountered bigotry when attempting to access public spaces, jobs and housing.

Certain neighbourhoods balked at sharing space with businesses that catered to the needs of Black porters. The issue came to a head in 1920, when a group of Victoria Park residents hired a lawyer to represent their objections to city council about a boarding house frequented by “coloured men.”

Ultimately, 472 inhabitants of Victoria Park signed a petition to city council that read: “We request that they be restrained from purchasing any property in the said district and any who may now be residing there will be compelled to move into some other locality.”

Council seriously considered this proposal, and wrote to 16 other Canadian municipalities seeking a precedent for sanctioned racial segregation. After ascertaining that no precedent existed, council refused the petitioners’ request. Informally, however, the mayor encouraged the complainants to harass real estate agents who sold to Black clients, writing in an article, “an aroused public opinion on such actions would accomplish more than any move the city authorities could make.”

Despite this encouragement of unofficial segregation, imagine the kind of city we would be living in if the decision had gone otherwise. Many Calgarians expressed shock in August 2010 when a rental ad on Calgaryfinder.com included the stipulation that no people of colour need apply. If city council had voted to entrench race-based discrimination in housing practices in 1920, that kind of ugly sentiment may have been merely business as usual in the city by the Bow. -Cheryl Foggo

Nixing the Expressway

Next time you’re in the start-stop-start-stop-wait-wait of driving through downtown, imagine the great expressway that could have been.

Imagine, in exchange for fewer minutes of gridlock, Calgary would be without Eau Claire, Chinatown, East Village, Fort Calgary, and any recognizable relationship between the downtown and Bow River curving around it.

Fair deal? What if City officials threw in a set of freight train tracks along that river?

City life, as life itself, is often defined by momentous decisions we make to not do something.

So it was with the move in the 1960s to scuttle a proposed relocation of the CP Rail mainline alongside the river, and then years later to stop plans for a downtown freeway. Until then, Calgary had seldom been willing to say no when Eastern railway bosses came calling. Calgary had also been unwilling to say no to unending progress of things that go vroom.

First came the rise and fall of riverside rails. City commissioners and rail poobahs loved a proposal that would liberate acres of downtown rail lands, remove the core’s southern barrier and make use of the weed-strewn dump that was then the Bow’s south bank.

The Local Council of Women and Alderman Jack Leslie called for riverside beautification instead, and won out as CP-City negotiations stumbled in 1964. Leslie became mayor a year later and brought about our beloved pathway system.

He also kept alive the rail scheme’s ugly stepchild – a highway that planning jargon from a more innocent age called the “Downtown Penetrator.” Six to 10 lanes wide, it would have converted several neighbourhoods to asphalt and interchange, but official Calgary wasn’t too attached to then-shabby Eau Claire or Chinatown.

That said, the transportation strategy that proposed a “penetrator” on 2nd and 3rd avenues also urged a pedestrian-only 8th Avenue and transit-only 7th Avenue. When you hear protests that Calgary is too car-centric, consider which of those 1960s-era plans went ahead and which didn’t. -Jason Markusoff

Pedestrian Friendly

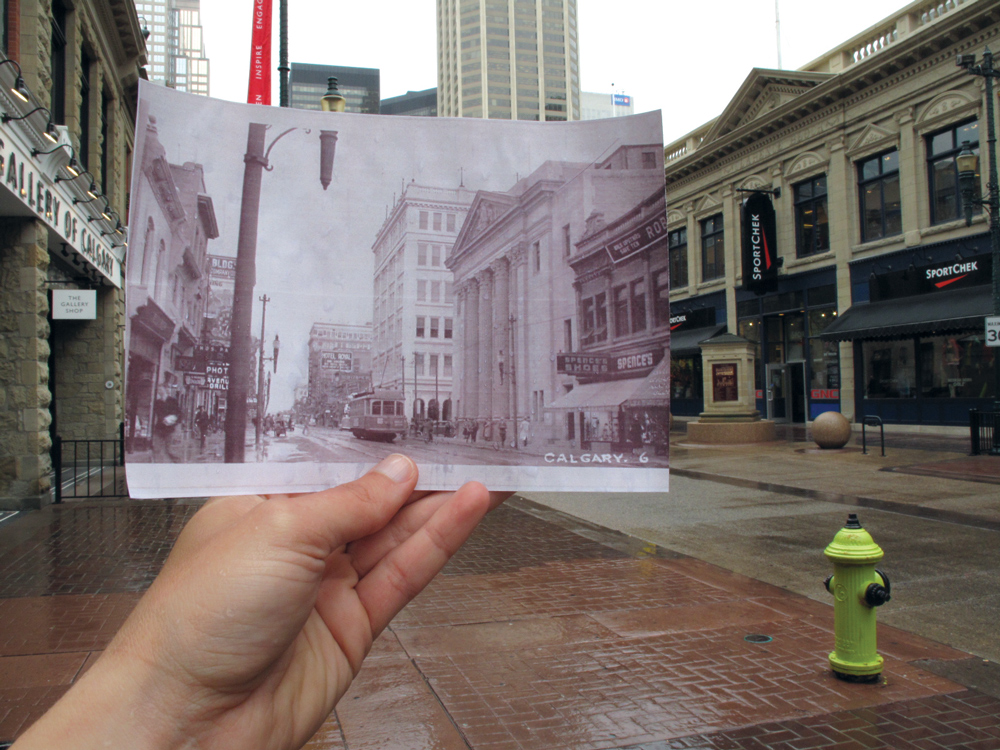

photograph courtesy of calgary public library

A downtown artery with some of the city’s best restaurants and shopping, Stephen Avenue (a.k.a. 8th Avenue) is the place to be for weekend walkabouts and business-day lunch hours. The decision to make a major portion of the street pedestrian-only during the day brought a new dynamic to the city, says d.talks co-founder Amery Calvelli.

“If there’s not a public realm, there’s a lot less interaction among citizens. It’s less of a city; it becomes less engaging. People don’t encounter others and there’s less social engagement.

“Frederick Olmsted referred to Central Park as ‘the lungs of [New York City],’ and I think Stephen Avenue is really the heart of Calgary. The heritage buildings are one part of it, but I see the heritage as the full street, all the cultural activities and all the trade that’s happened along that street over the length of time that it’s been a cultural centre.

“[Making it pedestrian-only makes it] more experiential; there’s more seating and there’s different variations of shops. You have everything from Winners to Holt Renfrew, chocolate stores to cowboy clothes, so you have a wide variety of things in a very condensed cube. It allows people to engage with others who aren’t necessarily like them.

“Strget in Copenhagen was pedestrianized in 1962, and it resulted in groundbreaking work in the bike and pedestrian realm of the city.

“It allows for more sociability for streets in the public realm. It allows people to see each other. It’s more of a public space, more of a centre, more vibrant.” -as told to Andrew Guilbert

Islands in the Stream

artistic representation of calgary municipal land corporation (CMLC).

St. Patrick’s Island, like Prince’s Island before it, is currently being redeveloped as public park space. It is scheduled to open in the spring.

William Pearce, chief inspector of surveys and Dominion Land surveyor, was called the “Irrigation Crank,” “the Czar of the Prairies” and not a few other choice names. Irascible and headstrong, he was respected by all and disliked by many. When he was honoured by the Kiwanis Club, he was given a walking stick – not to assist his walking, but to cudgel those who disagreed with him.

Back when Calgary was a windswept expanse of prairie, as bald as an egg, Pearce appointed himself chief crusader for trees. A passionate arborist, he believed trees could counterbalance this area’s aridity. Wanting to transform Calgary into the Forest City of Canada, he initiated an extended program of tree-planting, arranging for Central Memorial Park to be used as a nursery where Calgarians could buy seedlings for five cents.

Pearce dreamed of emerald pearls strung along the river through the city, and he relentlessly pestered the mayor and city council to promote parks. Promising that Calgary would protect them from unsuitable development, Pearce engineered the transfer of several islands in the Bow River from the federal government to the City of Calgary – for the outrageous sum of $1. Today, we know that was the best deal the City ever made, and it shaped Calgary’s green heart.

Without Pearce’s foresight, the islands in our river might have been eyesores instead of sanctuaries. Imagine our river without its island parks or pathway system. We would have no Calgary Zoo, no bowered home for Folk Fest, the River Caf or Shakespeare by the Bow; no oases for picnics and Frisbee games. That decision fostered our Bow River culture, with the banks a lure to urban fishers and stone-throwers, and the water itself enticing summertime rafting and paddling.

Stubborn and vigorous, Pearce may have been the most hated man in the city, but he ensured the natural beauty of the islands in our river. And legend has it that he looked, walking across the prairie with his practiced land-surveyor’s stride of 2,000 paces per mile, like a moving tree. -Aritha van Herk

Bridge of Trouble

photograph by jared sych

The decision to build the 130-metre pedestrian Peace Bridge, designed by Spanish “starchitect” Santiago Calatrava, fostered an increase in Calgarians’ interest in both public works and city council decisions, and raised Calgary’s international reputation, says Wordfest executive director Jo Steffens.

“It was a polarizing project for the city, but we’ve gone past that.

“It is absolutely a positive outcome. Just the fact that the bridge has become such a popular destination is a positive outcome. It gets people downtown more, it helps them interact with architecture and nature at the same time.

“The bridge has drawn attention to Calgary’s aspirations to become a more global city. I think it’s emblematic of Calgarians embracing art and culture and becoming more sophisticated and cosmopolitan.

“A bridge like this one took a very bold vision on behalf of city council. Cities need those bold visions for the future. Buildings are passed down to the next generation. It gives me great pleasure to imagine Calgarians 100 years in the future, when I’m long gone, still enjoying that.” -as told to Andrew Guilbert

Becoming Part of the Energy

It’s not like there was much doubt that Calgary was the energy capital of Canada before the Mulroney government moved the National Energy Board (NEB) to Calgary from Ottawa in 1991. The move was long overdue: industry leaders argued that Canada’s national energy regulator should have been headquartered in Calgary from the day it came into existence in 1959. Its Ottawa locale was convenient only for the bureaucrats drafting the nascent legislation.

The move to Calgary transformed the NEB into a leaner, meaner and more real world-anchored entity. Some two-thirds of the NEB’s employees did not make the move from Ottawa. Not all of them were replaced, but the newly hired came, for the most part, from Calgary and had been reared in the city’s entrepreneurial, versus Ottawa’s bureaucratic, culture.

Thus transformed, the NEB, in turn, transformed Calgary. As G. Bruce Doern and Monica Gattinger write in Power Switch: Energy Regulatory Governance in the Twenty-first Century, “An NEB staff member in Calgary is likely to have lunch with an energy business person rather than another bureaucrat.”

While the relationship between the oil and gas industry and its regulators is always a little tense – no matter how strict or lax the framework, industry would like less regulation and the regulator more compliance – a Calgary-based regulator better understands the on-the-ground needs of the companies and projects over which it has dominion. That’s good for the city’s (and the country’s) economy. Just as having a national regulator call Calgary its home is good for the city’s ego. –Marzena Czarnecka

Snow Angels

photograph courtesy of the calgary herald

Colynn Kerr with the plow he built to clear the Calgary pathways back in 1992.

In 1992, two avid cyclists began clearing snow from their commuting route along the Bow River Pathway using a homemade plow. Now, the City of Calgary plows 300 of the pathway system’s 800 kilometres. Snow and ice clearing are also key considerations in the City of Calgary Cycling Strategy, created in 2011.

Tom Babin is a bike commuter who literally wrote the book on winter cycling, Frostbike: The Joy, Pain and Numbness of Winter Cycling. Here are his thoughts on the development of clearer pathways in the city.

“There was a pretty decent pathway network [in the early 1990s], but cycling just shut down in the wintertime. Colynn Kerr and Jeff Gruttz [who became a founder of Bike Calgary in 2005] started clearing the path with a homemade plow. That went on for five years or so, and then the big St. Patrick’s Day snowstorm came in 1998 – the biggest one in a century. The volunteers tried to clear the pathway, but the snow was just too deep.

“Apparently, City Hall got a bunch of complaints because everyone had assumed it had been City workers clearing the paths. This was the turning point. There was a big public hearing at that time and it was just flooded with pedestrians, cyclists, joggers, people with strollers – all saying, ‘This isn’t just summer recreational stuff, this is infrastructure. It keeps us healthy. It gets us outside.’

“From there, the City started plowing a small section around downtown, and every year they’ve taken responsibility for more and more paths.

“It’s so important to the growth of cycling year-round to have these cleared routes. Anecdotally, the growth [in all-season cycle commuting in Calgary] has been amazing.

“Because more and more people are doing it, the attitude is more accepting. People don’t think you’re nuts; they consider it a viable thing.” -as told to Julia Williams

Rabbits and Rodeos

It wasn’t just the Clash asking, “Should I stay or should I go?” in 1982. A global surplus of crude oil gutted Calgary’s economy, leaving a generation of ambitious kids fleeing for greener pastures.

But not the brash punks that formed One Yellow Rabbit (OYR) and planted their freak flag here. The ever-evolving ensemble had the talent to make it anywhere but enough defiant bravado to stay put, seeing the opportunity gurgling beneath a culturally immature boomtown gone bust.

“It was an almost grubby, practical, economic decision,” to stay, says Blake Brooker, who, along with Denise Clarke and Michael Green, forms the rock-and-roll core of OYR. Rent was cheap, with foreclosed-upon buildings ripe for artistic squatting to establish the series of secret spaces that solidified the group’s mythology, audiences and balance sheet. The Rabbits intuitively “got” that, while Toronto, Vancouver, Chicago and New York might be cool, they offered an illusion of possibility, offset by fierce competition for living and creative space.

“You could rack up your 10,000 hours in Calgary in no time at all. It was like being the Beatles in Hamburg,” says Green, who has morphed from Calgary’s most-naked performer to the impresario of the High Performance Rodeo and the curator of Calgary 2012.

And, oh, what a wild time it was, an alchemic youth quake of movement, poetry, fine art, sound, music, film and theatre. “Creatively, we had this blank canvas stretched in front of us with nothing but the invitation to make our own mark, which was very powerful,” says Clarke, who joined the Order of Canada in 2014.

Three decades later, the Rabbits have pushed the boundaries of experimental performance art beyond existing borders, both geographic and creative.

“I have to be careful I don’t come up with too many grandiose, harebrained notions because Calgary will just let me do them,” says Green, who brought influential cross-genre artists including Laurie Anderson, Brian Eno, La La La Human Steps, Penny Arcade and Phillip Glass to Calgary, making it possible for local audiences to experience the world’s most challenging works, without having to leave home either.

“The rodeo gives us an in-house opportunity to keep our game sharp,” says Clarke, who, in 1997, launched her OYR offshoot, the Summer Lab Intensive, in which the Rabbits deliberately share everything they know.

More than 250 emerging and mature artists have been energized through the lab, and you can trace the Rabbits’ DIY DNA throughout the alternative YYC arts scene: Swallow-a-Bicycle, Ghost River, Eric Moschopedis and Mia Ruston, the Old Trout Puppet Workshop, Bee Kingdom, Arbour Lake Sghool, Springboard Performance’s containR, Beakerhead, Frivolous Fools Performance and Elaine Weryshko’s 10900.

But, perhaps more pivotally, the atmosphere of experimentation OYR fostered also created room for unique collaborations and experimental work from the more-mainstream companies including Theatre Calgary, Alberta Theatre Projects and the Alberta Ballet. OYR taught not only Calgary theatre practitioners but theatre audiences to be open to the novel and to choose the unexpected.

“We just feel nothing but possibility and energy with our colleagues and real, genuine wisdom,” says Clarke, still a young punk at 57. -Shelley Youngblut

All In For The Olympics

photograph by garth pritchard, cns files

Then-Calgary mayor Ralph Klein hitchhikes with Calgary Olympic mascots Hidy and Howdy.

Calgary has never lacked for guts, and the city-that-really-was-just-a-small-town first dreamed of hosting the Winter Olympic Games in 1957. The city bid, unsuccessfully, to host the 1964, 1968 and 1972 games.

When, under the leadership of Frank King, the Calgary Olympic Development Association (CODA, now WinSport) decided to launch a fourth bid for the 1988 Winter Olympiad, it was determined to not just get the games, but to make Calgary a world-class winter sport training centre in the process.

CODA’s long-view bid set the stage for the upward trajectory of Canada’s medal performance at all subsequent winter games, transforming – permanently – both Calgary’s physical and psychological landscapes. Canada Olympic Park, the Saddledome, the Canmore Nordic Centre, the Olympic Oval and the Nakiska Ski Resort are all legacies of the games: purpose-built for the Olympics and built to last – to train new generations of athletes.

And, while some past Olympic host cities have seen their expensive facilities fall into disuse, Alberta’s continue to be intensively used decades later.

Calgary’s performance – the games were televised, made money for the city, and showed future organizers how to harness grassroots volunteer power – transformed the nature of all future Olympic games.

Most importantly for us, the games changed the way Calgary saw itself. TSN’s Vic Rauter called it “Calgary’s coming-out party,” and boy was it ever – the city came out, to itself and to the world, as a world-class city capable of hosting world-class events, on a scale no one else dared to before. It got on the world’s radar and the world’s map – and it declared it wasn’t going to disappear ever again. -Marzena Czarnecka

Cultural Capital

photograph by mitch kern

Cloud by Caitlind R.C. Brown, part of 2012’s Nuit Blanche Calgary, a projec that received funding through the cultural capital program.

In 2011, the ministry of Canadian Heritage declared Calgary a Cultural Capital for 2012. According to Lois Mitchell, senior partner at Rainmaker Global Business Development and former co-chair of Calgary 2012, the designation was both a recognition of the city’s culture, a chance to showcase Calgary talent to a wider audience and a platform that came with funding to create a lasting cultural legacy.

“Our year as the Cultural Capital of Canada changed the country’s perception of Calgary. There’s a reason we’ve been chosen as the fifth most-liveable city in the world. I absolutely adore the Stampede, but there are so many other things visitors can come here and enjoy. People see us as culturally rich and absolutely more vibrant. Calgary was very fortunate to have [been designated a Cultural Capital]. It was the last one they did.

“Project grants were given to individual professional artists, registered non-profit arts and cultural organizations. Specifically, grants totalling $850,000 were invested into 144 projects and helped launch significant festivals that will continue for years to come, including YYC Comedy Fest, Doors Open YYC, Nuit Blanche Calgary and the National Jazz Summit.

“[One production supported by a grant,] Making Treaty 7, was about supporting and championing First Nations voices. Its purpose is to breathe new life into the founding treaty documents for Southern Alberta created 137 years ago through a theatrical presentation [that premiered at Heritage Park in September 2014]. It gave First Nations people the opportunity to tell their own story and forged new partnerships with The Banff Centre, The Glenbow Museum, Fort Calgary Heritage Park and more. Making Treaty 7 has since formed its own independent non-profit society to continue with these initiatives.

“We always think people come to Calgary for work, but people come here because they love the city, and that’s what Calgary 2012 was all about.” -as told to Meredith Bailey

Reuse, Renew, Repurpose

image courtesy of allied works architecture

The National Music Centre, currently under construction in the East Village, is scheduled to open in spring 2016.

After three years of construction, the Calgary Municipal Building, a 14-storey glass building connected to Old City Hall, was completed in 1985 off the east end of Stephen Avenue. Five years later, Old City Hall became the first legally protected heritage site in Calgary.

Since the completion of the Calgary Municipal Building, other heritage buildings have acquired modern additions, including the Biscuit Block, Fashion Central and, come 2016, cSpace. Andrew Mosker, president and CEO of the National Music Centre, now under construction incorporating the historic King Edward Hotel, talks about the significance of repurposing heritage buildings.

“After the [1988 Winter] Olympics, when the world came to see Calgary and formed a certain opinion of the city, Calgarians started to respond. Calgary started to think about the past and realize that it does matter – we matured as a city.

“With this kind of architecture, juxtaposition really shows. There are the values that made Calgary – hard work, volunteerism and can-do attitude – as epitomized in the [City Hall] heritage sandstone structure, and the other, modern structure that represents the idea that anything is possible for the future. It shows that Calgary has become a modern city, and yet it hasn’t forgotten its past.

“LocalMotive Crossing [in Ramsay] is a really good, recent example. Instead of building a replica extension with bricks made to look the same, [Patricia Davidson] added a very modern juxtaposition that gave it real character. The addition is full of slopes, curves, steel – it uses different architectural forms and different materials than the original.

“Another very good example is Theatre Junction Grand. Neil Richardson figured out a way to repurpose that building, even though there wasn’t much original architecture left. He exposed all of it, and you can see original paint and some original lighting fixtures. The old and new sit beside each other, and it’s very inviting to look at both and imagine the past.

“This was a huge inspiration to the new National Music Centre. We chose our new location because of the King Eddy. The NMC and the King Eddy came together harmoniously and very authentically because of its local legacy. We often joke that the King Eddy is the largest artifact in our collection and the modern building addition cradles it.” -as told to Karin Olafson

Birthing the Birth Centre

You don’t have to like the idea of natural childbirth to appreciate the significance of Diane Rach’s 22-year-old decision to open western Canada’s first free-standing birthing centre.

In 1992, Rach was an obstetrics nurse at the Foothills Hospital. She’d long considered becoming a midwife, but not only was there nowhere to formally train in Calgary at that time, the practice of midwifery (though legal) was entirely unfunded and unregulated in Alberta.

Through her involvement in Alberta’s burgeoning midwife movement, which holds to the philosophy that birth is generally a normal rather than a medical event, Rach learned about American-based birthing centres. Specifically designed and built for mothers who aren’t keen on a conventional hospital delivery but who can’t or don’t want to give birth in their own home, birth centres provide a place for labour and birth to occur in a relaxed, supportive, non-medicalized setting. Rach was so determined to offer the option that she plowed ahead without a hint of political backing and (to this day) no sign of subsidy. Against all odds, the Arbour Birth Center was born on October 1, 1994.

The Arbour, which was purchased and renovated by Rach and her husband with their own funds, is a retrofitted bungalow on 16th Ave. N.W. It offers clients a choice of three homey birthing rooms with ensuites, and also holds a waiting room and clinic. From the outside, it looks like a regular house – aside from the occasional jubilant sign in the window announcing that a birth has taken place that day. The centre is close to the Foothills Hospital – a key criterion for Rach who wanted to ensure quick transport for those mothers for whom medical intervention may be necessary.

While it would be difficult to prove that Rach’s birth centre actually ushered in today’s government policies regarding midwifery, there’s no arguing that she was in the vanguard; her decision was a harbinger of change for how maternal health care is approached in this province.

After 15 years, and countless meetings between Rach (who is now president of the College of Midwives of Alberta) and various health-care ministers, midwifery is fully funded by Alberta Health Services. Mount Royal University now offers a four-year Bachelor of Midwifery program, and Calgary is home to five fully regulated midwife clinics and collectives, each with a robust waiting list. The Arbour’s monthly birth numbers have recently increased to an average of 7.5 per month.

Rach was years ahead of her time. Before “choice” was a hot button word in health care in this province, she was determined to let Calgary women have a say in how and where to have a baby. -Jacqueline Moore

Hey, Ho, Let’s GoPlan

In 1992, the City of Calgary initiated the GoPlan, a three-year study to develop a long-range transportation plan. The GoPlan marked the first time the City considered the broad impact of transportation on communities and the environment, in addition to the usual considerations of cost and improved mobility. The expanded role of communities in the GoPlan decision-making process paved the way for citizen involvement in major projects like ImagineCalgary.

Bob Lang was a key member of various committees involved in the development of Calgary’s GoPlan. Lang is the current and, over the course of 32 years, longest-serving president of the Cliff Bungalow-Mission Community Association, and three-time president of the Federation of Calgary Communities.

“The GoPlan actually started with the grassroots organization called the Southwest Transportation Committee, facilitated by the Ward 11 alderman at that time.

“We eventually got city council to agree to a City study of the southwest communities from a transportation point of view, and then, all of a sudden, they decided to do the whole city. That is where GoPlan started.

“Three groups, [a citizen committee, a group from administration and a group from city council], came together near the end of the process and voted equally on what would go forward as recommendations to council. It’s the first and only time that I’ve ever experienced it, and I don’t think they’ve ever done it since.

“It showed that we needed to balance not only the mobility but the cost and the impacts on the community and the environment – this was the first time that this idea got documented.

“If they had literally taken what was in the Transportation Plan [prior to the GoPlan], it would have been a terrible mess…. There would have been huge impacts on communities, potential impacts on the environment and at very high cost.” For example, Lang says, there were proposals for river crossings through Edworthy Park and Sandy Beach, plus a transportation corridor through Inglewood.

“As a society, we’re becoming more enlightened. We’re realizing the impact – the negative impact, as well as the positive impact – from these roads. We need them, but we need them in such a way that they’re done to minimize the negative impacts.” -as told to Jay Winans

The Trade That Keeps on Giving

illustration by kelly sutherland

In 1980, the Atlanta Flames moved to Calgary, and centre Kent Nilsson came with them. In that first season he scored 131 points, still the team’s season record.

Wayne Gretzky once called Nilsson the most talented hockey player he’d ever seen in person. In 1985, at the height of Nilsson’s career, GM Cliff Fletcher traded him to Minnesota for a draft pick that the Flames used to pick up a box lacrosse player that nobody had ever heard of – Joe Nieuwendyk. (To this day, people still jokingly call him Joe Niewenwho?)

Four years later, Nieuwendyk scored 51 goals, and Calgary won its first and only Stanley Cup. Nieuwendyk became the team’s captain and represented Canada at the Olympics. Of course, as Nieuwendyk entered his own prime, the Flames, suddenly under pressure to shed the big salary he was due, traded him for a junior hockey player from just outside of Edmonton named Jarome Iginla.

We know what happened next.

If Fletcher hadn’t made that trade in ’85, there’d be no ’89 Stanley Cup. No Red Mile. Maybe there wouldn’t even be an NHL franchise in Calgary.

I’ll go one step further, though, and suggest that if we didn’t have an articulate black man as the face of the city’s team for more than a decade, there’d be no brainy brown guy in the mayor’s office today.

And there may still be some magic left in that string of trades. Let’s not forget that in the 2013 season, GM Jay Feaster sent Iginla to Boston for a first-round draft pick, plus a guy named Matt Bartkowski and another guy named Alexander Khokhlachev. Just after Boston announced the deal, Iginla kyboshed it. Instead, he went to Pittsburgh. We got a kid named Morgan Klimchuk. Morgan Klimchuk. Remember that name. -Chris Koentges

[Re]imagining Calgary

In 2005, the City of Calgary started the ImagineCalgary project, which would ultimately reach out to more than 18,000 Calgarians to develop a 100-year vision for the future of the city. The vision helped direct council and informed the creation of the 30-year plan for city development, Plan It, which council passed into policy in 2008.

According to Mayor Naheed Nenshi, who was first elected in 2010, Plan It and ImagineCalgary influence every single thing the City does.

“In Calgary, people think big. And, at that time, Mayor [Dave] Bronconnier was in his second term. [They] had solved a lot of the problems, or were working on solving a lot of the problems that led him to run for mayor in the first place and led that city council to be there. So then their question was, let’s turn our thoughts to the future; what are we trying to build here?

“ImagineCalgary really was the precursor to a lot of the community engagement we do now. It ushered in a very different way of working with the public. Not just traditional open houses where you put up a few tri-folds and hope people show up, and basically get folks with an axe to grind, [it turned it] into a really authentic way of talking to people about their hopes and dreams for the future.”

“One of the most profound things about ImagineCalgary was that, as we were talking to people, what was really surprising was the remarkable unanimity in their responses. It didn’t matter if you were inner-city or suburban, if you were self-described left-wing or right-wing, man or woman, young or old; it didn’t matter. People said exactly the same things. What kind of a neighbourhood do you want? ‘I want to live in a neighbourhood where my kids can walk to school, where I can walk to the store. Where my parents can have a place to live in the same neighbourhood so I can be close to them, and where my kids will go to school with kids who are quite different from us, so that they can learn about how the world works.’ People said all the same things. And so it led to a really profound question for the city council at the time, which is, if we know exactly what it is that people want, why aren’t we building that?

“At the time [Plan It] was put in place, we were experiencing over 100 per cent of our growth in brand-new neighbourhoods of the city. What that means is that existing neighbourhoods were slowly losing population. We were slowly emptying our city out from the centre. It wasn’t extreme, and most people didn’t notice it. But the trend was inexorable and obvious. And, in Plan It, it was decided the long-term goal for the city would be that 50 per cent of our growth would occur in existing neighbourhoods and 50 per cent would occur in new neighbourhoods. This was a huge, huge change…. So it was really a profound statement that said, you know, we’re going to do something different here.

“Last year, we went from a 110/-10 in terms of the percentage of growth in new areas versus existing areas, to something that was much closer to 60/40. So it has – really in a very short period of time – fundamentally shifted where people are living.” -as told to Kthe Lemon

[Correction: A previous version of this story stated that the more than 750 sites on the CHA Inventory of Historical Evaluated Sites are classified as protected heritage sites. It has been updated to state that while those more than 750 sites are on the inventory they do not necessarily all have any legal protection. More information on the heritage evaluation procedure and criteria can be found here.]