The State of the Visual Arts in Calgary

A bird’s-eye view of Calgary’s burgeoning visual arts scene

Calgary’s visual arts scene is vibrant, diverse and growing. Local visual artists, many of them Alberta College of Art + Design grads, are a collaborative, inclusive bunch. You can find their work in Calgary’s many artist-run centres, commercial and public galleries, pop-up exhibition spaces or prominently displayed as part of the City’s public art program.

Thanks to a strong economy, Calgarians spread across age groups and demographics are collecting art. Even the Glenbow Museum has refocused its mandate to spotlight its art collection. And, with the creation of Contemporary Calgary, the city is closer than ever to having its first major public contemporary gallery. When its new space opens, tentatively scheduled for five years from now, Calgary’s visual arts scene will finally be connected to the global art dialogue in a big way.

Buoyed by the energy of Calgary’s 2012 Cultural Capital designation and with the help of an arts-loving mayor, more and more Calgarians understand that art matters – it is an essential component to what makes a city great.

There’s a lot going on here – so much so, we can’t possibly mention it all. Instead, we take a bird’s-eye view and touch on some of what’s happening in Calgary’s visual arts scene. We look at what’s working, what’s not, what’s changing and what’s on the horizon. This is Calgary’s state of the visual arts.

Artist-run centres nurture local talent

Kyle Beal: Jokes Chokes and Gags in the Untitled Art Society’s main space.

From pop-up galleries to established artist-run centres, Calgary’s grassroots visual arts scene is thriving. It provides exhibition and professional-development opportunities for emerging artists, helps support and nourish established artists and continues to create new and exciting exhibitions and cultural events.

“There are a lot of very talented individuals in Calgary, but it’s pretty special in that competition isn’t as intense as it is in other cities,” says Ginger Carlson, programming coordinator for Untitled Art Society (UAS). “There’s a real sense of community here.”

UAS is an artist-run centre (ARC), a not-for-profit organization run by artists to provide greater opportunities for the public to engage with work that may not be seen elsewhere. Calgary has some of the longest-running ARCs in the country, including Truck Contemporary Art, Stride Art Gallery Association, The New Gallery and more.

Calgary’s ARCs provide exhibition space for artists. Many, such as UAS, focus specifically on emerging artists and offer support from the submission process through the installation of an exhibit to its eventual dismantling. UAS’s Arts Survival 101 lecture series covers topics like taxation for artists and finding a studio space.

“We act as a bridge for emerging artists entering into the professional world,” Carlson says. “Our interest is providing a space for experimentation where risky things can happen.” This kind of support encourages emerging artists to stay and create in Calgary instead of moving away.

UAS has 16 studio spaces abvailable to members at subsidized rates. UAS runs a main gallery space at 343 11th Ave. S.W. and also programs one of the seven window exhibits on the Plus-15 level of the Epcor Centre for the Performing Arts. The other window spaces are curated by Truck, Marion Nicoll Gallery, Stride, The New Gallery, Alberta Printmakers Society and Alberta Craft Council.

photography by jeff cruz

Jake Klein-Waller’s An Idle Warning in the Plus-15 window.

“It’s really wonderful to have that kind of collaboration and engagement in these small window gallery spaces,” Carlson says. “It changes every couple of months, so it’s something you can go and see repeatedly.”

Collaboration is the key to the ARCs’ continued success, which is evident in events like Nuit Blanche, a free, late-night contemporary art festival held in Olympic and Municipal Plaza on September 20, and Intersite, a three-day visual arts festival running Sept. 5 to 7, which UAS helped create.

“[Intersite is] absolutely free and open to the public, which is vital,” Carlson says. “It’s an open invitation to learn and talk about visual arts because it affects everyone in the city in some way.”

Culture is valuable

photography courtesy of trepanierbaer gallery

Chris Cran’s Candidates and Citizens, 2013, at the TrepanierBaer gallery.

Calgarians across age groups and demographics are buying art for their personal collections.

“At the moment, Calgary’s art scene is very lively and buoyant,” says Yves Trpanier, owner of TrpanierBaer gallery. “People have the resources and the interest, they recognize the work being presented here is very good and they’re interested in collecting and investing.”

TrpanierBaer’s spring exhibition by local painter and sculptor Chris Millar sold out in a matter of hours. “There were more than 300 people and it was a completely mixed crowd with many young people,” Trpanier says. “There’s amazing stuff being made here, and Calgarians are starting to talk about it. I’m encouraged.”

A strong art scene appeals to investors as well as collectors. Art can be a smart investment for savvy buyers because, over time, it has the potential to appreciate in value.

Trpanier has witnessed the ups and downs of Calgary’s arts scene. He founded TrpanierBaer, a commercial gallery specializing in Canadian and international contemporary art, with partner Kevin Baer in 1992. During that time, the Klein government cut back on funding to cultural institutions and the art scene suffered.

“When as a province we decided to go debt free, the cost was the decline of our cultural institutions,” Trpanier says. “People are starting to understand that you can’t take so much away and expect these places to survive.”

Calgarians’ renewed interest in buying art reflects a strong economy – people have the resources to buy it. But it is also connected to a larger picture of the value of art in the city and this includes the “art” of shared spaces such as architecture and public art.

“When you have world-class architects designing places like the Bow building, it puts the city in a different category in terms of what you aspire to,” Trpanier says. “These public places speak to people, it creates a greater sense that culture is valuable and it expresses itself in all kinds of different ways.”

Trpanier has consulted on several major public art projects, including a mural by local artist Ron Moppet in the East Village and a wall-mounted sculpture by Christian Eckart in Centennial Place that was commissioned by Oxford Properties. From the Bow building to Device to Root Out Evil, Dennis Oppenheim’s upside-down church sculpture that exhibited until 2014 in Ramsay, Calgarians are talking about public art and architecture.

“When you have tangible, visible projects you can go to and participate in, it really changes people’s attitudes,” Trpanier says. “The conversation around what it means to be a world-class city is happening in a real way because we have stuff to talk about now.”

Glenbow discovers a new, art-focused direction

photography courtesy of glenbow museum

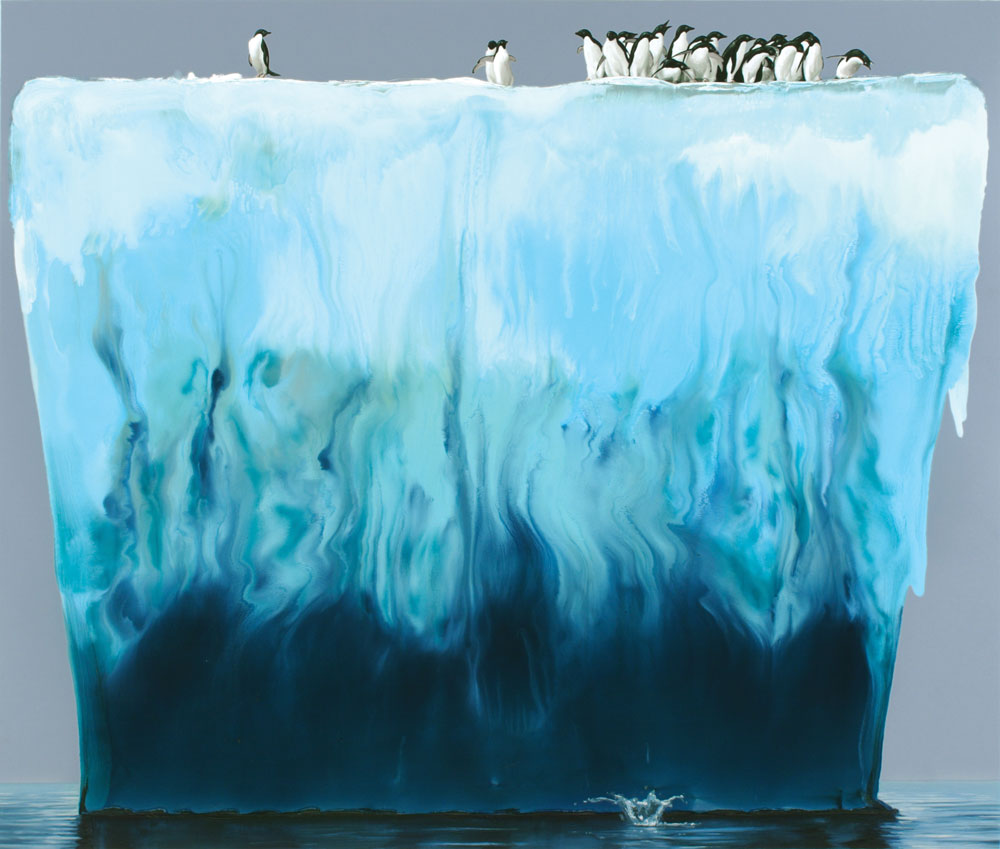

Alexis Rockman, Adeline, 2008, Collection of Robin and Steven Arnold will be shown September 2014 in the exhibit Vanishing Ice.

Founded in 1966 by Albertan philanthropist Eric Harvie, the Glenbow Museum is one of Calgary’s oldest cultural institutions, and it’s starting to show its age. With its 50th anniversary approaching, it needs a change to draw new visitors in and compel visitors of old to come back.

Throughout 2013, the Glenbow conducted an extensive audience-engagement survey. The good news is 98 per cent of Calgarians like the Glenbow. The bad news is many hadn’t visited it since grade school.

“I think for a lot of people the idea [that] Glenbow is a little old-fashioned and stuffy is still pretty fresh,” says Glenbow president and CEO Donna Livingstone. “The fourth floor hasn’t changed in 24 years, so, really, why would they come back?”

The survey also revealed Calgarians want an art museum to call their own. The Glenbow has the largest collection of historical, modern and contemporary art in Western Canada, three times that of the Vancouver Art Gallery. But its impressive art collection has never been the focus of its exhibitions.

“Although people don’t see us as an art gallery, that’s what we’ve been doing for 45 years and we need to be more overt about that,” Livingstone says.

So the Glenbow is now rediscovering itself as a “new kind of art museum.” Its recent art-focused exhibits include a retrospective on the photography of musician Bryan Adams (now closed) and the Made in Calgary series, an exploration of local artists through the decades.

The Glenbow has no plans to stop displaying historical artifacts from its million-item-strong collection, but you’ll see them alongside more historical, contemporary and modern art. “We have that sense of the past and history; our obligation is to take it forward,” Livingstone says.

For example, contemporary work from local glass-blowing art collective The Bee Kingdom was displayed this summer alongside pieces from the museum’s 1,800-piece pressed glass collection, which served as a historical echo.

“When we looked at our collections, we started to see the potential for this creative thread of art,” Livingstone says. “If it’s just a history exhibit, then you can look away, but, with art as the thread, you can continue to ask questions along the way.”

That creative thread extends to other media, including theatre. Calgary’s Verb theatre presented a new play, Of Fighting Age, in the midst of the Glenbow’s exhibition of the historic war art of A.Y. Jackson and Otto Dix as part of this year’s High Performance Rodeo.

“Seeing a play in the middle of art is not like reading label copy; you don’t come in and have a quiet moment with it,” Livingstone says. “We want Glenbow to be a place [where] you can not only look at art but also experience it in different ways.”

The Glenbow has already introduced bold and graphic signage, with future plans to install new flooring and lighting, reconfigure the entryway toward Stephen Avenue and eventually add a caf. The Glenbow is also becoming more playful in its old age. For the Made in Calgary: The ’80s launch party, audiences came dressed in 1980s attire.

“We had shoulder pads and the big hair; it wasn’t just to come look at art, it was participatory,” Livingstone says. “People want to mess around in the Glenbow. They want to dance here.”

Livingstone says it’s the Glenbow’s responsibility to take cues from the diversity and energy of Calgary’s local artists. “The arts scene is youthful and cheeky and bold,” she says. “It’s not a staid, old-fashioned city anymore, and my sense is that people have been waiting for the Glenbow to make up its mind about what it is and lead.”

Contemporary Calgary will connect the city’s art scene with the world

Trampoline, 2007, from the show Kim Dorland: Coming Home.

Calgary’s first major public contemporary art gallery is closer than ever to becoming a reality. Contemporary Calgary is the result of a merger between the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Institute for Modern and Contemporary Art and the Art Gallery of Calgary.

Without a major public contemporary art gallery to call its own, Calgary has remained out of step with the global art scene. It’s routinely overlooked for international contemporary touring exhibits because it doesn’t have the necessary space. For a city of more than a million people, it’s also a significant hole in Calgary’s tourist offerings.

“There hasn’t been a central institution that’s given the visual arts scene the weight it might have in other cities,” says Terry Rock, Contemporary Calgary’s interim CEO. “Calgary needs a space to host the most pertinent, interesting, challenging contemporary art that’s happening around the world. It’s a complement to the economic global dialogue we’re in, and it rounds us out as a city.”

Without access to a bigger, global conversation about art, Calgary’s visual arts community has been talking mainly to itself. Rock says a lack of funding as well as divisions between arts organizations are some of the reasons why the city has never had a major public gallery. But now that’s changing.

“We’ve actually got people who’ve been working separately, maybe even at cross-purposes, over the years who are now together,” Rock says.

The three partner organizations come to the table with experience, not all of it positive. In 2013, the AGC’s former CEO Valerie Cooper was sentenced to jail for defrauding the organization of $100,000. Rock says these legal issues haven’t negatively affected the future of Contemporary Calgary; instead, the incident was a catalyst for the entire visual arts community.

“It’s looked on as possibly the event that got everyone to focus,” Rock says. “With ACAD and the artists that we have here, the commercial dealers and the collectors, it doesn’t make sense that this isn’t working. People realized this isn’t good enough for our city.”

In March 2014, the City accepted Contemporary Calgary’s bid to take over the old Telus World of Science site in downtown’s west end. The organization is currently in a due diligence process regarding the 47-year-old building, exploring several possibilities for how to repurpose the existing space. Unlike the Glenbow’s sprawling historical collection, Contemporary Calgary will initially act as a non-collecting gallery exhibiting contemporary art.

Rock says there are no specific dates for Contemporary Calgary’s future plans, but the one-time Calgary Science Centre space offers a clear destination to focus on.

“When you see us host an event or put on an exhibition, it’s all in the service of that. I think it’s safe to say the timeline will be as soon as possible,” he says.

In the meantime, Contemporary Calgary is providing a taste of the future with exhibitions at C (the new name for the Art Gallery of Calgary) and C2 (formerly the Museum of Contemporary Art). The gift shop in C has been converted into a “vision space for Contemporary Calgary,” Rock says.

“If you’re interested or want to be involved, we have a place where you can come share ideas, offer help and be part of making this happen,” he adds.

Rock envisions the future gallery as a place where all Calgarians from different backgrounds and cultures will feel welcome, whether it’s for a quick visit after work or a place to spend a leisurely Sunday afternoon.

“Contemporary Calgary can make the connection between what’s happening in Calgary and the global contemporary-art dialogue,” Rock says. “It’s a conversation that we haven’t yet had an opportunity to be a part of.”

Calgary Arts Development widens the circle of support

photography by jordan baylon

Katy Whitt’s mural at artBOX, a CADA-supported art space on 17 Avenue.

In a city that champions entrepreneurs, Calgary’s visual artists are some of our finest examples. But that distinction is often overlooked, says Patti Pon, president and CEO of Calgary Arts Development (CADA).

“The misconception that visual artists have to be poor and starving for work drives me crazy,” Pon says. “In a city where we take pride in entrepreneurship, how do we begin to include artists in that conversation?”

Pon says for many years the city’s visual arts scene was divided between two ends of a spectrum: either grassroots, such as the city’s artist-run centres, or part of large institutions, including the Glenbow. Unlike the theatre community’s diverse ecosystem that includes emerging, small, medium and large theatre companies, Calgary’s visual arts scene has bubbled under the radar.

“In the visual arts community, that ecosystem hasn’t been as apparent,” Pon says. “There is a tremendous presence of visual artists who’ve chosen to stay and work in our community, but there hasn’t been as much of a through line between grassroots and institutions.”

Pon says there are positive signs that connections are happening, including the collaborative nature of Contemporary Calgary and the continued efforts of ACAD to find opportunities for its students in the city.

A diverse and healthy visual arts scene increases the ways Calgarians can connect with the arts, and CADA’s long-term arts-development strategy, Living a Creative Life, uses the metaphor of an eco-system to do just that.

“Living a Creative Life is about expanding the circle of arts champions,” Pon says. “We’re asking who’s in that bigger circle, what are the connections and how do the arts connect that circle?”

For visual artists, the strategy focuses on helping them create a sustainable life, which is essential to a healthy visual-arts scene. That includes connecting artists with affordable housing options, creating health and wellness programs targeted specifically to artists’ needs and introducing them to financial literacy programs, such as those offered by Momentum.

“These things don’t seem nearly as daunting as coming up with a giant individual artists grant program,” Pon says. “These are opportunities that contribute to them actually being able to make a life here.”

Living a Creative Life is about sharing ideas across sectors and disciplines. An artist can learn from an engineer and vice versa. It’s based on the belief that the arts play a fundamental role in innovation and that a healthy arts scene is a reflection of a vibrant city. To implement the strategy, CADA will act as a facilitator, connecting artists with opportunities and ultimately widening the circle of arts champions.

“The possibility I see is Calgarians acknowledging that the circle of support is bigger and that they may very well be in it,” Pon says. “Our hope is the notion of Calgary being a young, entrepreneurial city, with economic opportunities – all those things that people identify as reasons why they move here – will also resonate for artists and the arts.”

This article has been updated from its original to correct the spelling of Donna Livingstone’s name.