Of the roughly 5,000 days guide Barry Blanchard has spent in the mountains, only a couple are scorched into his memory. Run-ins with grizzlies are not so easily forgotten.

Though it occurred back in the early ’90s, Blanchard says one particularly vivid incident in the mountains of Banff National Park still feels like it happened yesterday. Blanchard recalls he was delivering instruction to two clients when one of them mentioned there was a bear nearby. “He said it so casually I thought I’d look up and see a little black bear ambling along the ridge a kilometre away,” Blanchard recalls. “But no, there was a grizzly coming onto our snow slope.”

As the bear closed in, the mountaineers attempted to create a distraction by throwing their packs down the slope. “The bear took a glance at the packs and kept coming. He was only three metres away and I just had to assume he was going to make contact with us,” says Blanchard. “I just yelled ‘slide!’ And I sat on my butt and held my ice axe in the air and accelerated down the snow slope and went launching off a 25-foot snow drop.”

After his clients dropped in behind him the trio scrambled down into a ravine and up the other side. From there, they watched the bear tear apart their packs. “Yeah, it was scary,” says Blanchard. “It was also amazing to watch this magnificent animal just play for an hour.”

Though more dramatic than the majority of human-bear encounters that take place in Alberta every summer, this one ended in standard fashion: hikers with a story and a tough decision for authorities – in this case the park wardens – who must weigh both bear and human safety against the public’s ability to enjoy the national parks (which, in essence, belong to all Canadians) and make the call as to whether trails in the area should be closed.

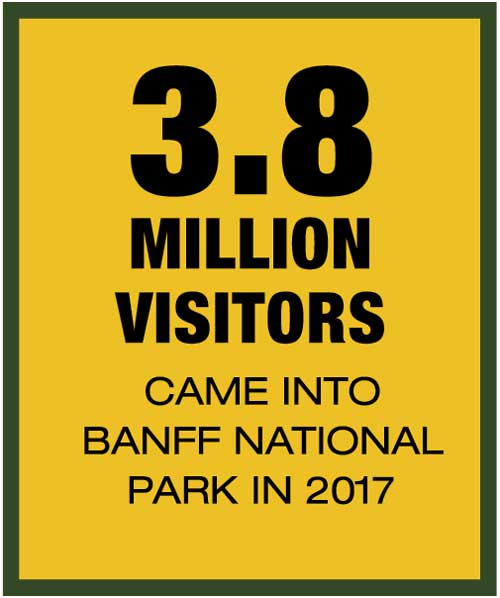

Trail closures are just one part of the answer to the much larger question of how humans and bears can safely share the landscape. But it’s a question that has taken on added urgency in the mountain parks near Calgary, which have seen high visitor numbers in recent years. Banff National Park recorded its highest visitation numbers ever in 2017, with approximately 3.8 million visitors through its gates. The numbers were up 2.5 per cent compared to 2016, which works out to approximately 95,000 additional individuals. The increase was due in part to the federal government’s decision to waive park fees as part of the Canada 150 celebrations, but visitation has been growing regardless, with the 2.5 increase between 2016 and 2017 consistent with recent year-over-year increases prior to that.

Regular users of areas like Kananaskis Country, a patchwork of provincial parks southeast of Banff National Park, have also witnessed trails getting busier every year. “We’re seeing parking lots constantly overflowing with people,” says Alberta Parks ecologist John Paczkowski. “We’re seeing an increase in bike traffic, in boat traffic, in paddleboard traffic, in hiking traffic. All across the board we’re seeing an increase of human use in Kananaskis Country.”

The Rockies’ appeal is undeniable; the allure of clear air, adrenaline and panoramic splendour is hard to resist. A one-hour drive westward from Calgary is all that’s required to enjoy world-class hiking, biking, canoeing, camping and other outdoor activities. Healthy tourist numbers are, by and large, something to celebrate – the tourism industry in Alberta generates over $8 billion in annual expenditures and employs over 127,000 people. However, humans invariably bring with them consequences for the landscape and the creatures that inhabit it. “It’s a great place to come and recreate, but that high-intensity recreation may have impacts and potential conflicts with wildlife,” says Paczkowski. “If we’re seeing different levels of human use in wildlife habitat the chances for conflict go up.”

Last summer was a busy one for wildlife officials, who implemented several lengthy and high-profile closures. Even for Canmore, a town used to bears in its backyard, the summer of 2017 was exceptional. A particularly significant incident was when an 18-year-old woman walking her dog near the reservoir just west of the town was attacked by a black bear. Woman and dog both survived the attack, though the woman required hospital treatment.

Paczkowski says that when it comes to deciding whether or not to issue a trail closure due to bear activity, authorities look primarily at the potential risk to public safety based on the frequency bears are observed in the area, the nature of bear attractants, and, in some cases, the species, age and class of bear. Officials had closed the area around the reservoir two weeks prior to the attack on the 18-year-old woman as numerous bears had been spotted there feeding on berries. The vast swath of popular recreation spots encompassing the area around Quarry Lake, Grassi Lakes and the Canmore reservoir was closed from late July until early September. While ignoring trail closures can incur a penalty, the woman was spared a fine because authorities deemed she had wandered into the area inadvertently.

Hilary Young is the Alberta program manager for the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, a Canmore-based non-profit. She says a number of factors combined to make last summer particularly eventful. “It was especially epic because of the number of visitors we had in the Bow Valley,” says Young. “The bumper berry crop last summer also meant that bears were drawn to the southwestern edge of Canmore for berries, bumping into human infrastructure and people on trails.”

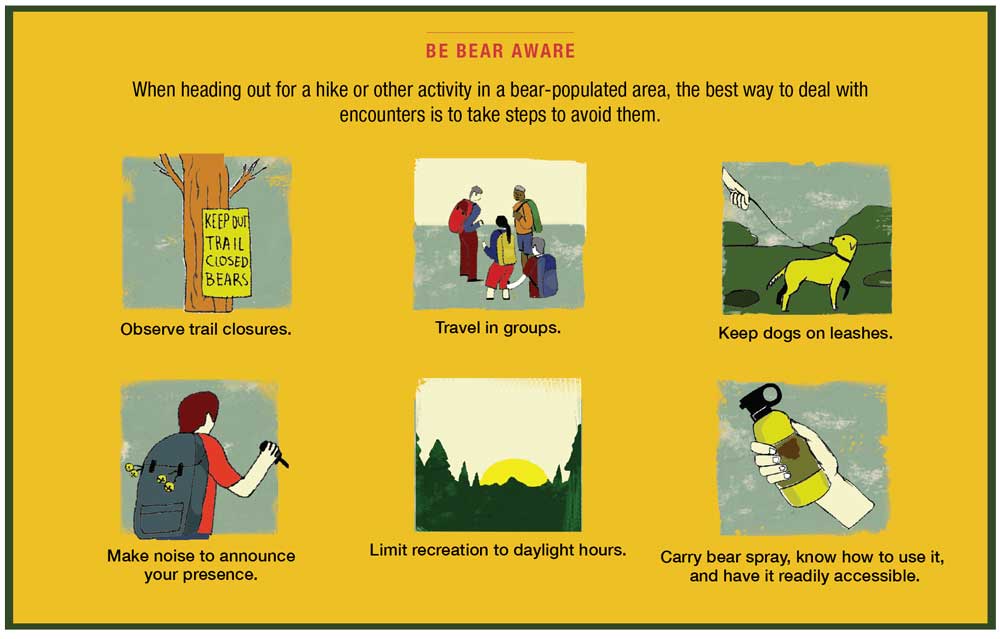

You don’t need to read about bear attacks in the news to know that encountering a bear is dangerous; it’s understood viscerally. Besides observing trail closures, those who enjoy spending time in bear country know to take safety precautions such as travelling in groups and making lots of noise to lower the chances of an encounter. In the event that a human-bear encounter can’t be avoided, having bear spray readily accessible (and knowing how to use it) is considered the best defense.

That the bears are also in danger during such encounters is less obvious, but something Canmore residents were tragically reminded of last summer. Bear 148 was a six-year-old female grizzly who spent the majority of her time in Banff National Park. She was habituated to people, meaning she had lost her fear of humans, but generally left them alone. Things changed, however, when Bear 148 started moving eastward toward Canmore, drawn to the area because of the great berry crop. “She was attracted to heavily populated areas where people are recreating on trails, so there was more conflict,” says Young.

After a few encounters with people around Canmore, Bear 148 was relocated to Kootenay National Park in early July, but she quickly returned to the Canmore area. Though she would bluff-charge trail users, she never actually made physical contact with anyone. Following a week of near daily encounters with hikers and joggers, the question about what should be done with the curious and troublesome bear took on more urgency. There were rumblings that if Bear 148 were involved in another serious incident, Alberta Fish and Wildlife officers would be required to euthanize her, prompting Banff residents Bree Todd and Stacey Sartoretto to start a petition urging the government to leave the bear alone. “She belongs here and on our landscape, the only home she knows, and should not be executed for simply being a bear. She is surrounded by millions of people yearly and does a pretty good job of avoiding them,” read the petition, which has since been signed by more than 37,000 people.

“I think it really tugged at people’s heartstrings and they felt an attachment to her,” says Young. “The feeling was that [the bear] was doing what she could; she was giving people warning. She was just unlucky enough to end up in a territory that was filled with people.”

Eventually the government decided to trap Bear 148 and relocate her to the remote Kakwa Wildland Provincial Park northwest of Jasper. Survival rates after such translocations are generally low, but Bear 148 seemed to be doing okay in the weeks following the move (her movements had been tracked by GPS collar since as far back as 2014). By mid-September, however, she wandered across the British Columbia border and the bear’s troubles, which began with human encounters, ended the same way. She was shot by a hunter (legally) mere months before B.C. permanently banned hunting grizzlies in December of last year.

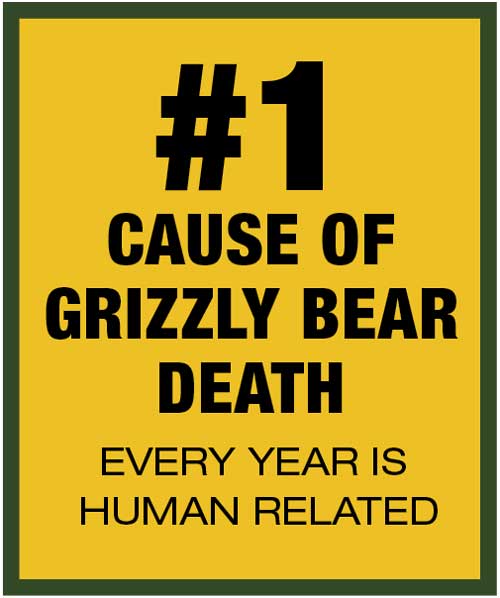

Young says that on top of losing a breeding-age female, a blow to the province’s threatened grizzly population, the death was upsetting for the many who had followed Bear 148’s story. Young is careful to point out that the various jurisdictions did all that their policies allowed them to do to help Bear 148. But the fact that it still wasn’t enough has cast a spotlight on the issue of bear-human coexistence. “Within the Bow Valley, specifically, I would say coexistence is more visible than it has ever been,” says Young. “Every year the number-one cause of grizzly bear death is human-related in some way or another. Many local Bow Valley residents acknowledge that we need to better understand how our recreational pursuits affect our ability to coexist with wildlife.”

Canmore’s roughly 14,000 permanent residents aren’t going anywhere and though the town is taking measures like removing attractants such as fruit trees, that may not be enough to limit conflicts, especially considering further development in the area is all but certain. The subject of limiting how people recreate in bear country is also contentious in the Bow Valley, Young says. Having predictable trail closures during berry season, however, is one measure that could help. “There may be times, such as during berry season, that it’s more important for bears to use those areas and people to stay out of them,” says Young. “People may have to adapt and use different recreational areas and trails while bears are feeding heavily in certain areas.”

As part of the response to this past summer’s events, the mayors of Banff and Canmore convened a roundtable of representatives from the Ministry of Environment and Parks, representatives from the towns of Canmore and Banff, federal and provincial parks authorities and conservation and wildlife-education not-for-profit organizations in an effort to reduce human-wildlife conflict in the Bow Valley. The roundtable’s technical working group has since met for five hours every two weeks and the roundtable hopes to have a series of recommendations ready to present to the community by the end of May.

Looming over the discussions is the idea that there is a threshold of human use beyond which bears will start to disappear. It’s an idea that is being talked about more and more among Alberta Parks managers and conservation biologists, according to Cheryl Hojnowski. The Canmore resident recently received her PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, for her research into wildlife usage of human-dominated landscapes. During the summers of 2014 through 2016, Hojnowski conducted grizzly-bear research in Kananaskis Country as part of her PhD studies. Previous to that, she worked with community organizations conserving tigers and leopards in eastern Russia.

While Hojnowski believes such a threshold exists, the challenge is determining what that level of use is before coming up against it. Her own research, conducted in conjunction with Alberta Parks, focused on how grizzlies navigate areas heavily frequented by people. Hojnowski used vehicle counters, trail counters and camera traps to monitor human activity, and collars to track grizzly-bear movements. After sifting through three years of data she was able to conclude that bears adjust their behaviour in response to the type, timing, location and intensity of human activity. One bear in particular clearly avoided the parts of her home range that incorporated popular campgrounds and recreation areas within Peter Lougheed Provincial Park on weekends, when these areas were at their busiest and most crowded. “It almost seemed like this bear could count to seven when you look at her locations on weekdays versus weekends,” says Hojnowksi. “That [the bears] are adjusting to us is an incredible thing, when you think about how people are changing wildlife behaviour in a way where they are learning how to navigate us.”

As impressed as Hojnowski is by the animals’ artful dodging of people, she is concerned about the consequences of increased human recreation in wildlife habitats. If, as her research indicates, bears adapt their behaviour to avoid people, then it helps for them to have predictable quiet times and places where they know they can avoid humans. Restricting recreational trail usage to daylight hours and making sure park visitors stay on marked trails are both measures that Hojnowski believes would go a long way toward helping bears adapt. “These bears are trying to avoid the times and areas with highest human activity and if we allow the whole landscape to become high human activity, we may not have these animals out there anymore,” she says.

That is an outcome no one wants; seeing these iconic animals in their element – from a distance – is a universal thrill. But as people continue to flock to the mountains, Hojnowksi believes at some point Albertans will have to make a choice. “I think that we have to decide what we value,” she says, “and if we value wildlife on this landscape then I think we need to accept limits on how we use that landscape.”