We live in a data-driven world, one in which almost every industry uses some measurement of its outcomes to evaluate whether companies are reaching their goals. Many of us also use and track data to see if we are meeting personal goals — whether that be miles run, weight lost, numbers of books read or days in a row that we meditate. The field of psychological counselling, however, has been particularly resistant to measuring outcomes and tracking results with numbers. The reasons are mostly rooted in the idea that the therapist-client relationship is inherently subjective and the belief that a professional psychotherapist can tell when a client is getting better and when they aren’t.

But an alternate view holds that those who are undergoing counselling and psychotherapy are better served when they are given the chance — by way of a standardized questionnaire — to evaluate whether their treatment is helping. One method, known as Feedback Informed Treatment (FIT), provides therapists with a quantitative measure of whether their methods are working and the client is getting better, and it’s being championed right here in Calgary.

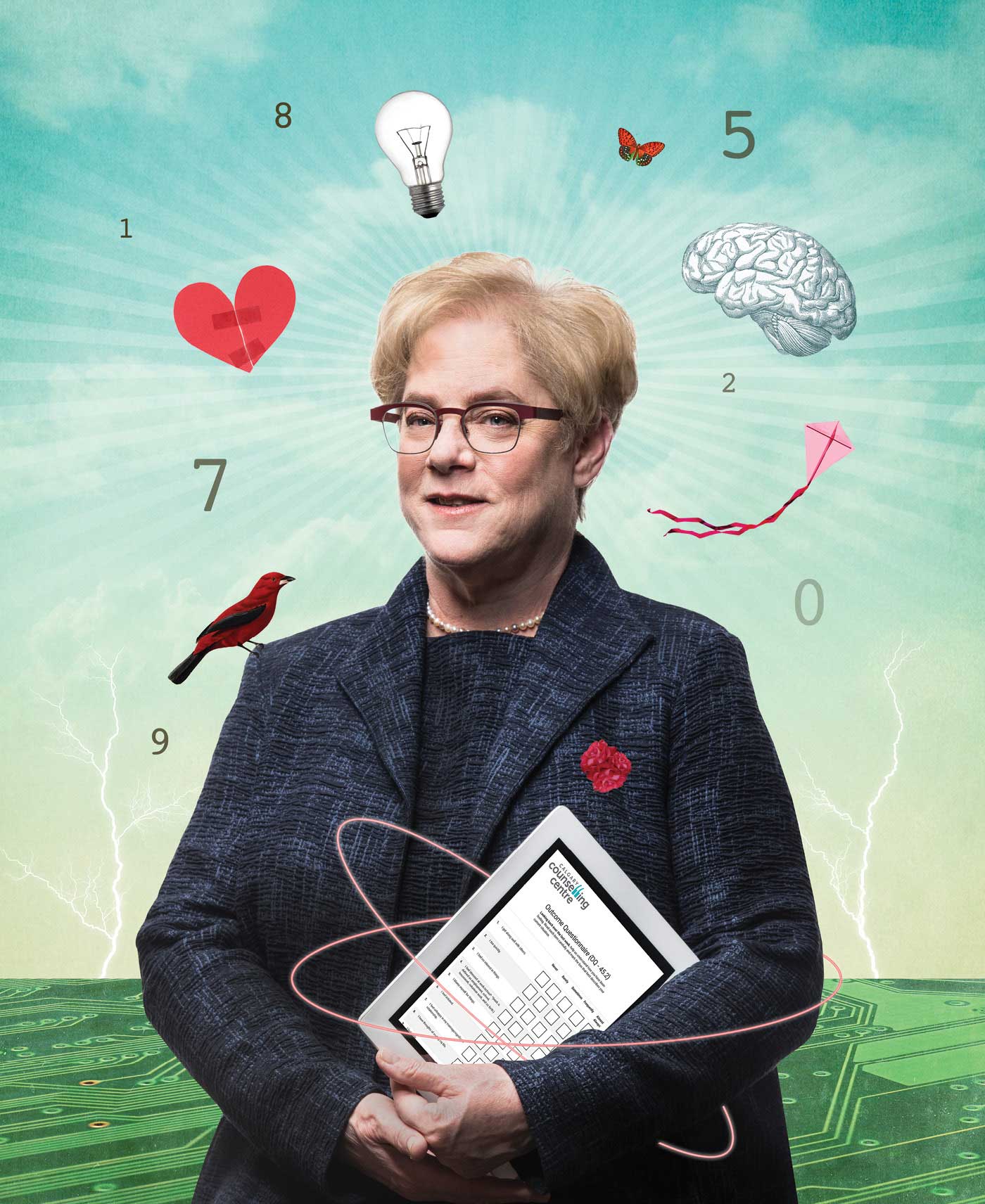

The Calgary Counselling Centre (CCC) has gained worldwide recognition for implementing this approach. In the mid-2000s, under the direction of its CEO, Dr. Robbie Babins-Wagner, the CCC began using a mental health vital signs questionnaire to track each client’s progress. Within the FIT model, each client is given a score for the level of their distress based on their answers to the questionnaire — the higher the score, the higher their distress. The global average score at a first counselling session is 72 and a score of 63 or lower indicates the client is no longer in distress. Figures released by CCC for 2017 showed the average level of distress for its clients to be 76.9 at the first session and 63.6 at the last session — a statically significant 13.3 per cent improvement. 44.6 per cent of CCC clients reported improved mental health or recovery after counselling and 95 per cent of clients benefitted from service. According to the CCC, its 2017 results exceed all published benchmarks by 32.6 per cent.

Babins-Wagner’s adoption of FIT and the success CCC has seen as a result have earned her adulation from FIT advocates and researchers around the world. But even those who don’t subscribe to the idea of FIT have a grudging admiration for CCC’s numbers. Hearing the word “visionary” isn’t uncommon when Babins-Wagner’s name comes up.

“One of the amazing things about Robbie is that at the centre she’s instituted a number of very progressive reforms in terms of tracking outcome data and is using it in very progressive ways,” says Tony Rousmaniere, a member of the clinical faculty at the University of Washington and author of a 2017 article about FIT published by The Atlantic, titled “What Your Therapist Doesn’t Know,” which heralded Babins-Wagner’s work at the CCC. “For example, all the staff get a quarterly report of their outcome data, which is something that is basically not done anywhere else in the world, but is incredibly valuable, and I imagine 10, 20 years from now everyone will be doing.”

Babins-Wagner was hired as director of counselling at CCC in 1992. Her background is in social work with undergraduate degrees in psychology and social work from McGill University in her native Montreal. In 1978 she and her husband Neil Wagner, a technology consultant, left Quebec in the Anglophone exodus following the election of the Parti Québecois. They settled in Ottawa, where Babins-Wagner, then 24, got a job with the Children’s Aid Society and set about getting her Masters’ in social work at Carleton University. One year into her program, the couple went to Banff for a ski holiday and dropped in on a professor friend at the University of Calgary. Two weeks after they returned home, Neil was offered a teaching job with the U of C faculty of business. “Why not?” they decided, “it’s for only two years …”

Babins-Wagner also ended up at the U of C. She started working as an instructor at the university in 1982 and in 2011 earned her PhD in social work there. She remains part of the faculty as an adjunct professor and sessional instructor, teaching social policy, social work research and social work practice. “The policy and the research are interesting because those are courses that typically social workers don’t want to take,” she says. “I didn’t want to take those courses either, but over the course of my career in both those areas, I’ve become very interested in how they’re connected to clinical work, how they kind of work hand-in-hand. And the policy pieces teach us skills about how to advocate for change, either within an agency, in a community, provincially and nationally. So those are the skills that I love teaching social workers how to use.”

Babins-Wagner’s interest in research and its connection to clinical work as well as advocating for change have shaped her career. Shortly after being hired at the CCC in 1992, Babins-Wagner made her mark by helping to figure out why the Centre’s domestic-violence counselling program had consistently low attendance. The program launched in 1982 and by 1992, out of every 100 men who registered only 30 were actually following through and showing up at the group sessions. Working with a team of evaluators, Babins-Wagner added test measures at the beginning and end of group sessions, but even after a year of evaluations they were no closer to improving the numbers.

Then, a staff member requested permission to deviate from the intake procedure, which involved filling out a cumbersome form detailing various types of partner abuse. The form was a standard questionnaire that counselling centres across North America were using at the time for domestic violence programs. While completing the form, this prospective client had revealed that he himself was a survivor of sexual abuse. Though it carried the risk of repercussions, Babins-Wagner okayed the staff member’s request to sideline the form and instead work with this disclosure. “I told her I’d take full responsibility,” she says.

That incident proved to be a catalyst. A year later, CCC had changed its entire intake approach when it came to domestic violence-related cases: initial sessions were spent talking with the men, developing a relationship and rapport with them, rather than delving straight into the questionnaire. Following that procedure change, the percentage of men attending group therapy went from 30 to 85, with 80 per cent completing the program.

Those results have remained stable ever since.

This success with changing procedures emboldened Babins-Wagner to try it with other group programs, to similar success, and in 1996 she was promoted to CEO. By 1999, the CCC had set its sights on improving the results of the individual counselling programs. This presented new challenges; people come to counselling for a wide variety of problems (Babins-Wagner says there are around 120 identifiable problems that lead people to seek counselling, and the CCC deals with around 30 to 40 on a day-to-day basis). The question was whether CCC would have to develop new protocols for each of the reasons a client might come in or whether there was one over-arching protocol that could improve results for all clients.

That overarching protocol would prove to be FIT.

Babins-Wagner first learned about FIT from the book The Heroic Client: a revolutionary way to improve effectiveness through client-directed, outcome-informed therapy. She promptly brought in one of the book’s co-authors, Scott D. Miller, for a workshop at CCC. From 2002 to 2004 she tried out different data-driven approaches. At the end of the trials, CCC staff voted to implement outcome feedback forms consisting of 45 questions that clients would answer before every session and a short questionnaire evaluating whether the client’s needs had been addressed at the end of each session.

Even though staff had voted in favour of the approach, not everyone was happy. Many counsellors had a difficult time adjusting to the reliance on data instead of their expertise to indicate whether counselling was working. “Part of it is our training and socialization,” says Babins-Wagner. “We’re not trained to be accountable to numbers and external forces, we’re trained to be accountable to individual clients.”

Many counsellors, not only at CCC but everywhere, not only feel they can tell what’s going on with clients, they see that ability as a valuable part of the job. However, a 2005 study found that while clinicians estimated that 85 per cent of their patients were recovering, actuarial studies showed only 15 or 20 per cent were recovering. “Part of it is that as professionals we’re socialized to trust our instincts instead of having a more formalized way of being able to check if clients are actually doing well,” says Babins-Wagner. She believes that FIT data provides a good check on the limits of instinct and serves as a “wake-up call.”

Certainly, the reveille sounded by the data-informed approach was not music to everyone’s ears. In 2008, the CCC found that required questionnaires were only being given to 40 per cent of clients. Babins-Wagner put her foot down, reminding counsellors that outcome data would not be used in their work reviews, but that it was still a requirement. “We didn’t get a ton of negative feedback or pushback, but by Christmas [of 2009] about 40 per cent of [the licensed professional] staff left,” she says.

Cathy Keough, the CCC’s current director of counselling initiatives, was among the 60 per cent who stayed, and recalls her CEO’s steadfastness during that challenging period.

Babins-Wagner was the “captain of the ship,” Keough says. “She was solid and she never wavered and that made an incredible difference, because if there had been any wavering we wouldn’t have been able to do what we did.

“I was the clinical supervisor at the time, and it was a difficult time for sure, and I remember going to her on many occasions and saying, ‘how do you know that this is the right approach?’ And she would say, ‘I’m sorry I can’t give you more, I just know the clients deserve it.’”

A big part of what sets Babins-Wagner apart from her peers is her willingness to be vulnerable and transparent with her own results, says Rousmaniere. It’s a characteristic he says is rare among high-level psychotherapy professionals who tend to hold their results close to their chest. “I think she walks the walk, absolutely,” he says. “She is just very dedicated to helping her centre clients get better and she’s not as concerned about her reputation, or whatever.”

Babins-Wagner’s work has netted her numerous accolades, including the 2015 Lieutenant Governor’s Circle on Mental Health and Addiction True Leadership Award and the University of Calgary Arch Alumni Achievement Award. She has also been approached by Veterans Affairs Canada, Kaiser Permanente in the U.S., and the Institute for Social Work at the University College of Copenhagen, among others, to consult on FIT. “Everybody wants to know what are we doing; what’s the magic ingredient,” says Babins-Wagner. “There is no one magic ingredient. It has really been about focusing on the clients’ progress, changing practice and changing culture.”

Being a public face for FIT and for CCC goes against Babins-Wagner’s comfort zone of being “a real introvert, actually,” who reenergizes by spending time alone, reading, and credits a group of close friends for being able to draw her out of her shell. Though retirement beckons with travel and grandparenting, she won’t be heeding that call quite yet. (“Well, I’m having too much fun,” she says.)

It also might have something to do with her growing more and more comfortable with that word, visionary. “When people started saying this to me, five, seven, 10 years ago, I would say, no, that’s not me. I’m just doing my work,” she says.

“I can live with it now.”