Kris Vester’s parents started their family farm on a quarter section of land west of Carstairs in 1977. His mother was from Germany, his father from Denmark, and Kris is the sixth of their eight children. “We were the little army of farm labourers,” Vester said. He left the farm after high school to pursue a career in academia, but returned in 1998 with his wife Tamara. In 2012, they took over the farm and renamed it Blue Mountain Biodynamic Farms.

Blue Mountain now produces 120 varieties of organic vegetables, cereals and herbs, and also raises chickens and hogs. The fields were bare when I visited last January, but the Vesters’ pigs were dozing in their pens snorting tiny clouds into the chill morning. During the summer, the Vesters’ hogs graze on prairie grasses and seedless crops. This adheres to their nature. “A pig digs just like a chicken scratches and a cow grazes on grass,” Vester said. The happy hogs of Blue Mountain reflect the Vesters’ overall philosophy toward food production, and the ethics of many such small-scale farmers, who strive to provide local consumers with what Vester calls “good, clean, fair food.”

We should all eat this way: locally grown, humanely raised and sustainably produced food is better for the health of our bodies and our planet than food from feedlots and factory farms. More and more Calgarians avoid the big-box grocers to champion producers whose world view more closely adheres with their own. They crowd Calgary’s farmers’ markets, purchase food from small-scale farms and ranches and buy shares in community-supported agriculture programs, all to help build and sustain an ethical local food system.

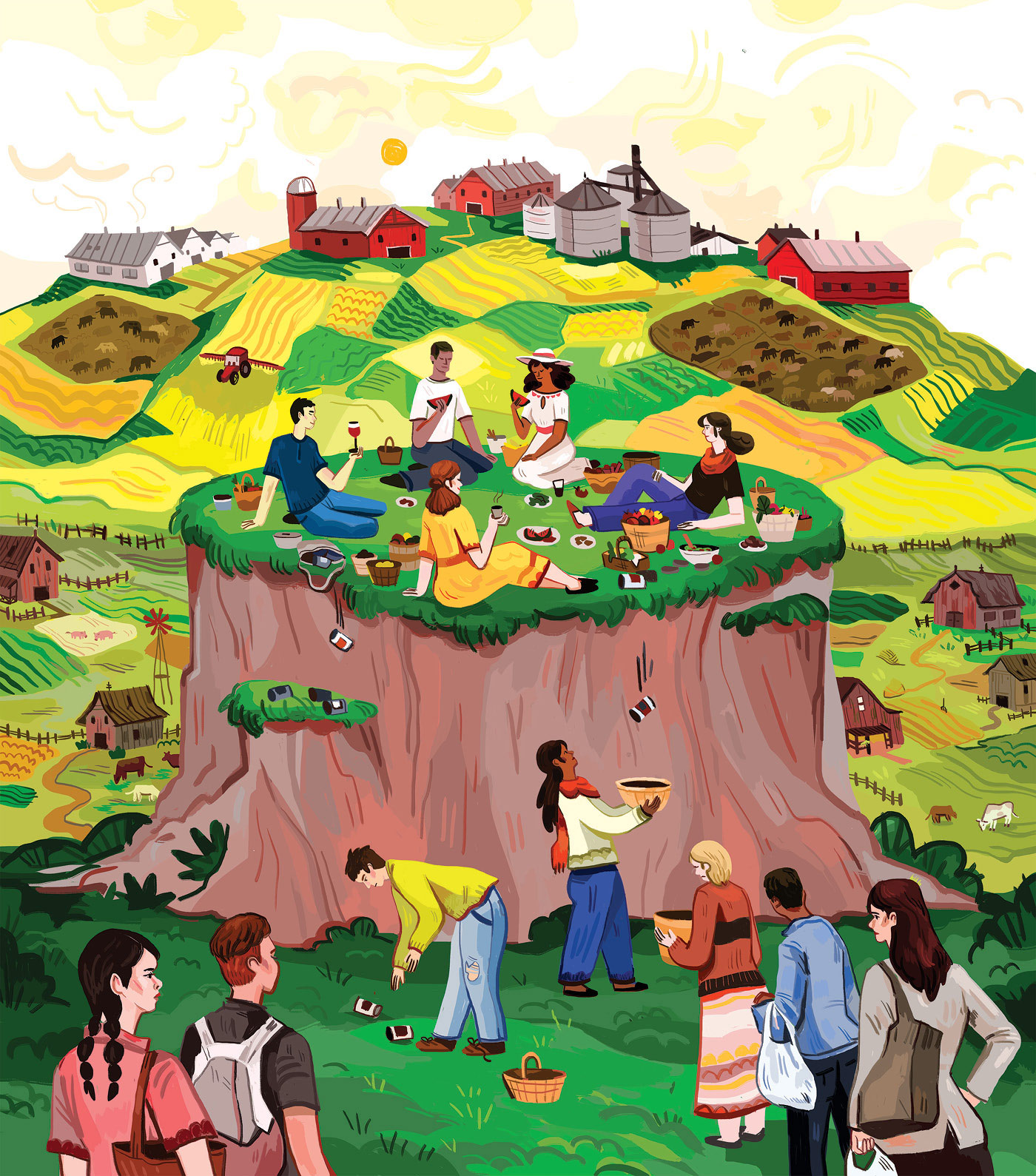

But this system is not as ethical as well-meaning shoppers might believe. Such ethical food remains inaccessible to many Calgarians, especially those with lower incomes. The farmers’ markets’ regular patrons might not see the high barriers standing between Calgary’s poor and those fresh-vegetable stalls, but that inaccessibility is in itself, unethical.

Obtaining any food at all can be a struggle for the truly downtrodden. Often the programs designed to help people access food come up short in volume, let alone in considerations of the ethics of the food’s origins. Rebecca Sandberg knows this more than anyone. She holds certificates in Food Security and Sustainability Management from Ryerson University. She is also a single parent of three small children. “I have both book smarts and street smarts,” she joked.

Sandberg believes many Albertans misunderstand the nature of poverty. “Most people who are middle class, and who work hard, have this idea that people who are low income are lazy,” she said. Sandberg sees that mentality influencing not only attitudes, but public policy as well. For example, the Alberta government publishes a table of the average cost for healthy food in the city of Edmonton. According to the November 2018 table, the weekly “nutritious food basket” for a family of four is $225.91, or a little more than $900 a month. However, Alberta’s income-support programs will provide that same family with total monthly benefits of around $1,600 if they’re working, or $1,759 if they have barriers to work — either way, not nearly enough to buy $900 worth of food, in addition to other necessary expenses. For these families, paying for rent and heat means not buying nutritious food, let alone paying the premium often charged for sustainably produced local food.

“The government has outsourced the problem to the food banks,” Sandberg said. Last fiscal year, the Calgary Food Bank helped more than 180,000 people and distributed more than 66,000 emergency food hampers. “They do really, really good work,” Sandberg said, but access to the Calgary Food Bank can be problematic. “Lots of people assume if you can’t eat, you can go to the food bank and they’ll give you food. Well, that’s not the case.” The Calgary Food Bank provides users with up to seven emergency food hampers each year, and only three without a referral from a community agency. Each hamper is designed to last for seven-to-10 days so, at best, the food bank provides only 10 weeks worth of food per year.

Calgary Food Bank users won’t find much “ethical” food in their hampers, either. Food banks and other charity-driven providers rely primarily on grants and donations, mostly of non-perishable canned and processed items, many of which are nutritionally poor. In fairness, food banks strive to feed the most people possible with limited public funds and donations. This means sourcing cheaper food. But few Calgarians need good, clean, fair food more than those who are struggling.

Food assistance can also come at a cost to personal dignity. In order to get help from charities such as food banks and soup kitchens, low-income people must line up and expose themselves to the stigma of being poor, then take what the relatively wealthy have cast onto a donation pile. In this system, poor people must eat what richer people don’t want.

Sandberg, who volunteers delivering food bank hampers, said the perishable food is often already nearly perished. Cultural issues are also sometimes ignored. “I’ll have weeks where I’m literally dropping off a bag of random pork to a Muslim family,” she said. “‘Here is your bacon and your sausage and your ham. Have a good day.’ I feel like it is insulting.” Sandberg knows many Albertans don’t believe the poor deserve any better than almost-expired yogurt and forbidden pork and beans. They should be happy for the handouts — beggars can’t be choosers, as the saying goes. “This is the opposite of social justice,” she said.

Price remains the highest barrier to choosing ethical food, even for those who don’t rely on the food bank. Locally grown, sustainable food costs far more than conventional food. But according to Kelly Hodgins, who has a background as a food systems researcher and used to work as a farmer on the Sunshine Coast, ethical food is not overpriced or marked up. The price of local food reflects the true cost of small-scale labour-intensive farming, not a higher profit margin. The price of a tomato at a farmers’ market stall likely reflects the actual cost of growing that tomato.

Farmers like Kris Vester, who calls himself a “proud, peasant farmer,” make philosophical decisions about their production that often actually lowers their profits. “They have chosen to go against the conventional market forces that would tell them to get bigger. To buy up their neighbours. To get more automated,” Hodgins said. “Farmers are not jacking up prices to pour more money in the bank so that they can build their kids a swimming pool and build a mansion. This is not the face of a farmer.”

The problem, then, isn’t that local food is “expensive” but that cheaper food can be found elsewhere. The sort of conventional automated factory farms that stock the meat counters and produce sections at big supermarkets don’t share the small-farm ideal of staying small. Their pigs don’t dig. But raising sows in giant barns on slat floors is cheaper, just as synthetically fertilized crops grow faster than organic. Those large-scale food corporations can afford to sell their products at a lower cost.

All of this leads to a system where poor farmers grow food for rich people, while rich farmers make food for the poor.

But price is not the only obstacle to ethical eating. “Anyone can get a bag of lentils,” Hodgins said. “Kale and onions are pretty cheap.” Many people simply don’t have the time to cook healthy meals from raw ingredients. A working single parent is more likely to make Kraft Dinner out of a box than craft a dinner out of a bag of market vegetables. And while the City of Calgary’s “Calgary Eats!” action plan helps enable citizens to grow their own food — either on their own property or in one of Calgary’s 169 community gardens — Calgarians without the time to cook likely don’t have the time to garden.

Many do not have the knowledge to do so either. In the 1980s, Sandberg’s stay-at-home mother prepared healthy meals from scratch every night. “We never ate out of boxes,” she said. But Sandberg’s mother spent half her day on food preparation and came from a generation that learned how to cook. This is no longer the norm. As more women joined the work force, the demand for processed and packaged food increased. “Then it flipped,” Sandberg said. “We became reliant on the processed, packaged food because we don’t know how to cook anymore.” Gardening skills diminished, too, as people lost the time and space to plant their own food.

Of course, these deficiencies are not exclusive to lower-income Calgarians. A wealthy business owner may just as easily be useless in the kitchen, and a busy lawyer might not have the time to garden. But those in a higher wealth bracket can often obscure their lack of time and food knowledge. They can eat in the kinds of restaurants that use local ingredients. They can take out and order in. They can subscribe to meal-kit services like Rooted or HelloFresh.

In several Calgary neighbourhoods, there is nowhere nearby to buy fresh food at all. Sandberg has identified 26 “food deserts” — areas with limited access to healthy, fresh and affordable food and grocery stores. And although the chain grocers increasingly carry some organic and local foods, sustainably grown local food is often even harder to attain. The city’s two large year-round farmer’s markets, Calgary Farmers’ Market and Crossroads Market, are difficult to reach for anyone without their own vehicle. Only two bus lines bring shoppers to Crossroads, and the one bus that serves the Calgary Farmers’ Market does not run on the weekend. “They have organic, and they have sustainable, and they have local, and they have blah, blah, blah,” Sandberg said. “They have all those things, but getting there is crazy. That’s an hour of your day that usually you spend cooking or working your two jobs.” People with mobility issues may request rides from Calgary Transit Access, but the service allows only two shopping bags per rider — hardly enough for a family grocery run.

There are Calgary agencies and social justice groups that work to fill the structural gaps in the food system and bring down the barriers to access to local, sustainable and organic food. One Monday last December, I watched as volunteers with the Fresh Routes’ Mobile Food Market loaded plastic crates of food onto tables at The Alex Community Food Centre in Forest Lawn. Boxes of yams, potatoes, apples and kale. Banana bunches and bags of sliced bread. Dozens of eggs and tiny tomatoes in Ziploc bags. Once they brought in all the food, the volunteers fixed price cards to the crates with metal clips, while a kid who couldn’t have been more than 13 years old set up a table with a cash box and a roll of plastic shopping bags.

Fresh Routes (formerly the Community Mobile Food Market) aims to increase access to fresh, healthy and budget-friendly food, especially to residents in Calgary’s food deserts. It operates regular pop-up markets in 10 Calgary communities in locations like Village Square Leisure Centre, seniors’ housing facilities in Bridgeland and East Village, and the Sunalta CTrain station. Fresh Routes buys most of its products from a local wholesaler and sells them at prices below those of the big-box retailers. The nimble mobility of the market, and the service of the volunteers, allows Fresh Routes to keep its prices low.

In addition to affordability and accessibility, Fresh Routes provides a level of dignity to its customers. “We don’t want our clients to feel they are using a social service,” said Roxanne Pham, Fresh Routes’ former market lead. Anyone can buy from Fresh Routes, not just those carrying referrals declaring they are poor enough to shop there. The produce on offer is fresh and unbruised, not donated waste. Rather than lining up for a hamper, Fresh Routes’ customers can sniff the tomatoes and thump the melons just as at any farmer’s market. Fresh Routes also prices items by unit rather than weight so that people who need — or can only afford — a single orange or a couple of tomatoes don’t feel any pressure to buy a bagful.

The sense of belonging extended from the mobile market tables to the dining room of The Alex itself. The centre hosts the Fresh Routes’ mobile market on the same night as their weekly community dinner. When I visited last winter, around 50 neighbourhood diners filled the dining room — some single men, some families, all bulky in their heavy coats. There was no lining up at a stainless-steel counter. No hairnetted staff scooping stew onto a Styrofoam plate. As soon as The Alex’s guests sat down, servers brought them the night’s offering: meatloaf with butternut squash and a spinach-orange salad, all elegantly composed on a real plate with real silverware. Servers returned to clear away the dirty dishes when the meals were done. A donation jar stood at the front of the dining room, but nobody was obliged to contribute.

In addition to the Monday night dinners, The Alex serves lunch on Wednesdays and a Friday morning breakfast. Approximately 100 diners on average show up to each meal, though numbers fluctuate throughout the month. They serve fewer people when income support cheques are delivered and more when rent is due. Many of the diners know each other. I eavesdropped on their card games and their holiday plans. For Joanna Tschudy, The Alex’s garden skills coordinator, such community-building is key. “You come in, and there is a level of ownership,” Tschudy said. “You grab a cup of coffee or tea on your own. But then you grab a seat. Start a conversation. Meet new people or sit with friends.” These meals provide a balm for those who are struggling, either financially or emotionally. “The meals help with the social isolation people might be facing,” Tschudy said. “It has a huge impact. Just sharing a meal together is massive.”

The Alex sources most of the ingredients for these meals, and for the other programs the centre runs, from the Calgary Food Bank. But The Alex has also fostered relationships with local food suppliers. Poplar Bluff Organics supplies the kitchen with donated potatoes, carrots, parsnips and garlic. The Alberta Hunters Sharing the Harvest Association provides The Alex with wild deer, elk and moose meat donated by local hunters and processed by an Alberta Health Services-approved butcher.

The Alex’s most inspiring donor is Mohamed ElDaher, a refugee who fled the Syrian Civil War with his family in 2016. As soon as they arrived in Calgary, Mohamed plowed under his backyard in Ranchlands to plant vegetables. A local entrepreneur gave ElDaher five acres of land to farm near the airport. Now ElDaher rents 11 acres of farmland and operates four greenhouses where he grows a diverse variety of vegetables, from familiar beans and lettuce, to the sort of green chickpeas, Arabic cucumbers and fava beans his family ate in Syria.

ElDaher gives away the bulk of what he produces. Last year, he donated spinach, beans, peas and green onions to The Alex along with hundreds of tomato, pepper and eggplant seedlings for The Alex’s gardening programs. Once he builds his fifth greenhouse, he plans on giving more. ElDaher also sells his produce directly from his farm as a “pick-your-own” operation. No doubt he deserves our business. So do the Vesters and other local farmers who opt to grow locally and sustainably. “We need to support those guys,” Hodgins said. “At the farmers’ market you are paying to support the local community. You are paying to support the environment. You are voting with your dollar for a healthier planet.” At the same time, Hodgins warns against vilifying the conventional food system. “When we are facing these huge issues of climate change and feeding 10 billion people by 2050, we’re in dangerous territory if we’re trying to advance this alternative niche food system as the one solution, because it can’t be,” Hodgins said. “We cannot, through this system, feed the entire world.”

Perhaps we need a more realistic approach to food security, locally and globally. “Rather than trying to fix our ‘broken’ conventional food system by creating a brand new one, why not fix what’s broken with the conventional food system?” Hodgins said. “Let’s identify what those things are that are making people turn away and want to get or grow food in a different way. Then fix them instead of creating a new system that is not accessible to everyone.”

The problems are easier to identify than solve, of course. Maybe governments should mandate that industrial farmers account for the widespread consequences of their production. If giant feedlots had to clean the water they contaminate with manure run-off, say, they might employ more environmentally sensitive and ethical production methods. Perhaps sustainable farmers should be designated essential workers and granted a guaranteed income. Maybe poorer Calgarians need more reliable access to charity food providers and higher income support. For her part, Sandberg hopes to open non-profit community food hubs in Calgary’s food deserts that offer members free donated fresh produce, low-priced staple foods and access to a fully equipped community kitchen.

In the meantime, Calgarians need to consider the barriers surrounding access to sustainable and local food and to making a truly ethical food system. Those who have the privilege of shopping at farmers’ markets need not sneer at those who, for a number of reasons, don’t. Being tone-deaf to the realities of access that are structurally imposed on people is unfair.

Even Kris Vester buys milk and cheese at Costco during harvest season when he has a crew of farmhands to feed. He understands the challenges many Calgarians face when trying to feed themselves. “Those people putting themselves forward as ‘woke’ could show some compassion,” Vester said. “If you are already feeling like you are barely getting by, why wouldn’t you choose the cheapest food? You have to. Especially if you have children. We could all use a little more compassion in this world.”