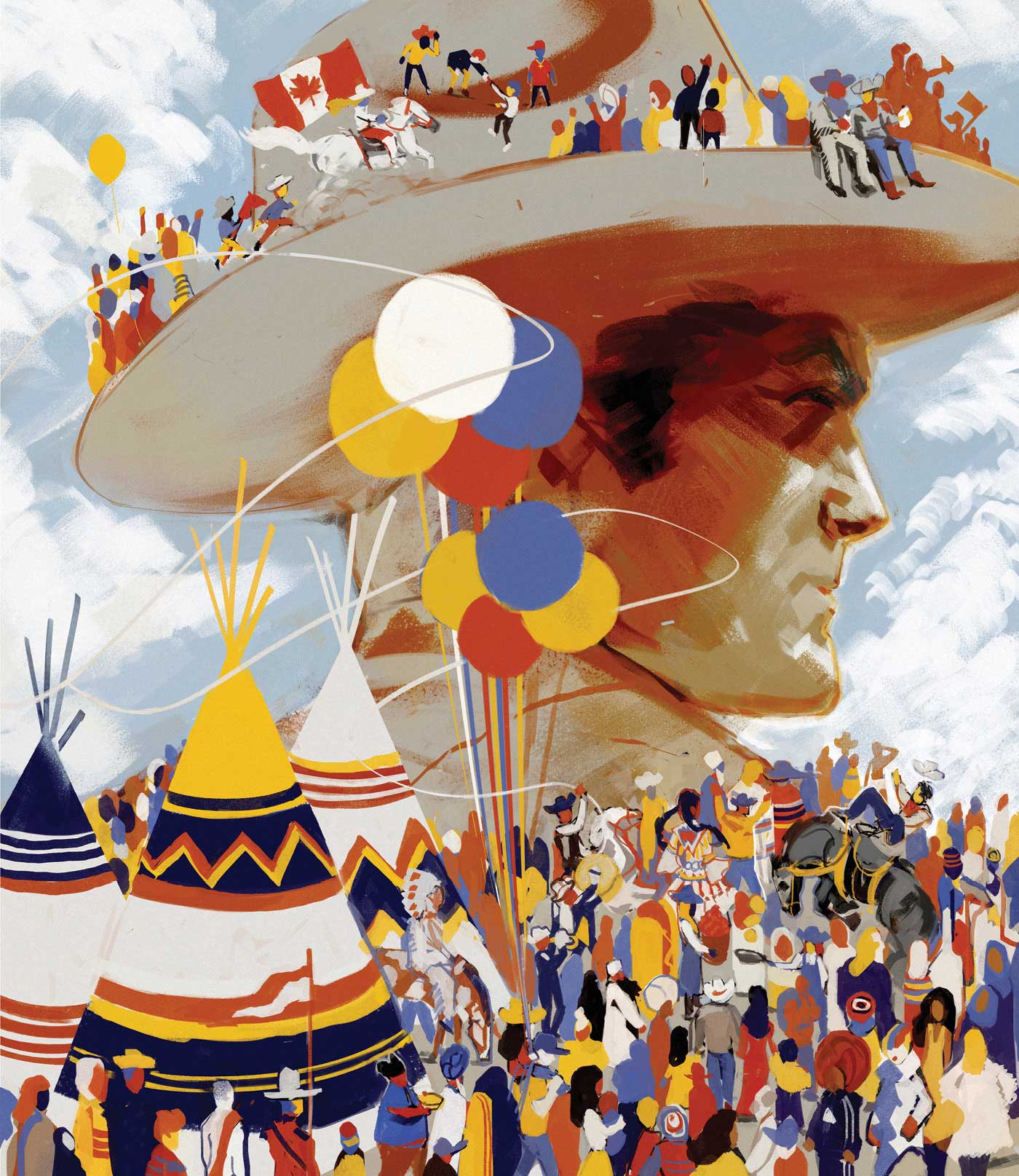

The Greatest Outdoor Show on Earth is a celebration of Western culture and values wrapped around a midway, a shopping centre, the city’s largest music festival, community pancake breakfasts, corporate schmooze-fests and more. But at Stampede’s heart is nostalgia for a ranching and agricultural past that grows increasingly distant for many Calgarians. How Stampede maintains relevance as the city grows and changes will be pivotal to its future.

There is no such thing as the Calgary Stampede. At least, not in any unified, coherent way. It’s truer to say that there are many Stampedes. The Stampede contains multitudes. The cowboys focused on intense competition, the kids with cotton candy on the midway, the noisy young people getting excessively drunk, the guys hawking the latest time-saving kitchen gadgets, the families lined up for free pancakes, the corporate folks in jeans at exclusive boozy breakfasts — all of them are experiencing the phenomenon known as Stampede, regardless of whether or not the events are officially sanctioned or on the actual grounds.

Indeed, part of the Stampede’s power has been its ability to be all things to all people. There have been many evolutions and the sheer scale of the 10-day festival, the non-profit organization that oversees it, and the cottage industry of adjacent events, has exploded since the first iteration in 1912. Because it splashes out of the grounds with parties, concerts, community parades, breakfasts and more, no single person or group defines it or owns it completely.

And yet, it is in some way cohesive because, at its heart, it has remained a celebration of cowboys and horses and agriculture and rodeo — a tribute to “Western” heritage, values and mythology. Sure, the Stampede is all about community and bringing people together, but you’re strongly encouraged to come together wearing a Stetson and shouting ya-hoo!

However, in a city continuing to diversify and evolve from its stereotypically white, conservative, ranching roots, can the cultural juggernaut that is the Stampede remain relevant without its own process of change?

It’s one thing to be all things to all people in a relatively homogenous town, as Calgary was for much of the 20th century. But with more than a third of Calgarians identifying as not-white, and with people coming from all over the world to make a new life here in a city less and less tethered to ranching and agriculture, the question of the long-term appeal of something like Stampede seems reasonable. What happens when there are not only more people, but more kinds of people, with different backgrounds and perspectives? Can the same strategy still bring success?

Warren Connell, the chief executive of the Calgary Stampede, who began his career with the organization in 1984, says these questions have been on the radar for some time. “One measure of success that we certainly look at is, when we run these events, does the Stampede visitation actually reflect the identity of Calgary?” he says, then adds, “we certainly do reflect Calgary.”

According to the Stampede’s survey numbers from 2014, 27 per cent of park visitors were visible minorities and 77 per cent of immigrant Calgarians believe the Stampede is relevant.

Connell argues that people of most cultures understand the importance of agriculture, and he points to outreach programs and summer camps aimed at immigrant communities — particularly youth — as one of the ways in which the Stampede makes an effort to bring new Canadians into the fold. It’s a sensible strategy: Jyoti Gondek, city councillor for Ward 3, who says diversity issues in the city are important to her, notes that many newcomers find their way in a new place through what their kids get interested in. The question of inclusion goes deeper than just who attends Stampede, though.

Much of the Stampede is a celebration of Western heritage and a bygone era of ranching and pioneering in the West. But so much depends on perspective. In the case of Stampede — or, indeed, Canada in general — one side’s remembrance of a golden past can be seen by others as willful erasure of painful truths.

“Reconciliation” means different things to different people, but at its core is the notion that Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples, both past and present, is pretty awful and needs a fundamental rethink. In many ways, the central myth of the Stampede — the celebration of the up-by-the-bootstraps ranchers who tamed the wild west — neatly aligns with Canada’s benign self-image: kind, friendly white settlers who came here to build communities and share the land with their Indigenous neighbours.

“There’s a Western-settler philosophy that believes, ‘we’re a kind people,’” says Indigenous activist Michelle Robinson, “when the truth is the history is not kind at all.”

When asked about reconciliation, Connell lists his credentials for allyship: he was staff liaison to the Stampede’s First Nations committee for 25 years, and that to his knowledge he is “the only staff liaison to receive an Indigenous name from all five tribes.” He also grew up as an “army brat” near the Tsuut’ina reserve, so “my background goes pretty deep,” he notes. “This subject is actually near and dear to my heart.”

Connell notes that Guy Weadick — the American promoter who sold the idea of the Stampede to Calgary (and other cities) — managed to negotiate an exemption to the restrictive Indian Act to allow First Nations people to leave the reserves and bring their children to the Stampede grounds to participate, and to display some of their cultural practices, which, at the time had been outlawed in public. The legacy of this early First Nations inclusion, Connell says, can be found not only at the Elbow River Camp (you can read more about the Elbow River Camp here), but also in the Stampede’s various outreach and hiring programs.

For Robinson, however, the equality presented by Stampede is a myth that doesn’t reflect the lived experiences of Indigenous people. “You get to showcase your outfits, but you’re still harassed and bullied by the Calgary police, you’re still harassed and bullied by security. So: not one of ‘us.’ We’re still ‘othered’ even within the Calgary Stampede,” she says.

Robinson sees positive potential for the Stampede in the city, but only if the organization gets serious about actively creating inclusion. Given the role of ranching and agriculture in depriving Indigenous people of their territory and well-being, she argues the Stampede both could, and should, be a national voice for reconciliation efforts.

“They don’t see a role for themselves in reconciliation, when the irony is they could be leading the charge and the conversation,” says Robinson.

But Connell stops short of believing the Stampede should use its massive voice and platform to advance reconciliation or educate the public on Canada’s oppression of Indigenous people. “The Stampede’s history is really about successfully moving forward and building an inclusive community and a greater community. So why would the Stampede go out and focus on the ills of other groups when … we consider our success to be about facilitating going forward and partnerships and our collective future?” he says.

Likewise, Councillor Gondek warns there could be backlash if such a thing is handled poorly. “I would want it to be part of [Stampede’s] regular operation and their regular strategic planning and their vision, more so than as part of the festival. Because once you make something part of the 10-day exhibition, it becomes commodified,” she says.

One inclusive development in recent years is Pride Day, an event intended to draw the LGBTQ+ community to the Stampede. It began as Gay Day, an informal gathering organized by a handful of friends, but has since been rebranded as Pride Day and scaled into a major event at Nashville North.

“The Stampede can often be seen as a macho, sort of rough, very straight, one-minded kind of event, and we wanted to try to break that open a bit,” says Charles Macmichael, the primary organizer. “We started the event as a way to bring folks from the LGBTQ+ community together to sort of get over the hump. It’s the same hump that prevents people in the LGBTQ+ community from really feeling comfortable on team sports.”

The culture around Stampede’s core events of rodeo and agriculture — frequently conservative, religious and hypermasculine — creates a space that can feel threatening to people who are marginalized or targeted in society at large, let alone at a rodeo. “There’s a lot of misconstrued, heteronormative macho behaviour that they might not feel comfortable around,” says Macmichael. “I liken it to if you are in a new city and you turn a corner and are a little bit lost, and you walk down a street where you get that vibe that you might need to stand a little straighter or walk a little faster or puff your chest out a little more to kind of prevent something from possibly happening to you. That’s, I think, what a lot of LGBTQ+ people feel when they go to an event like the Stampede.” Pride Day, with its safety-in-numbers principle, drag performers and cheeky name tags, helps draw in people looking for a safe space.

Though not originally from Calgary, Macmichael is a fan of the Stampede, and speaks highly of his experiences working with the organization in recent years as Pride Day has received its support.

“The Stampede has been very supportive, but also — I think for the right reasons — wants to keep this as a partnership as opposed to a corporate takeover, if you will,” says Macmichael, who describes the relationship as very positive, but also says that there was initially “reasonable amounts of hesitation on both sides.” That said, Pride Day has certainly been a success, and Macmichael would like to see it grow and evolve further.

If Pride Day is one example of how the Stampede can evolve, it’s worth noting that this event began as a grassroots effort, not as an initiative by the Stampede to reach out to the community. But there are some shifts that may need to come from within. As the Stampede ponders the future, it must consider not only demographic changes but also the shift in values and priorities represented by younger generations. Millennials are, in broad terms, more progressive than their elders, and more likely to be concerned about social issues, equality, sustainability, climate change, animal welfare and what’s in their food.

So can the Stampede bend itself around these concerns without alienating its core demographic? “We are mindful of that and have been on a path of inclusion for a great number of years,” Connell says of these shifts. “The Stampede does recognize that it needs to continue to reflect the community’s needs.” More food options have appeared on the midway for those with dietary restrictions or ethical concerns. And the Stampede boasts of its high rating for animal welfare and care. Recycling and waste-diversion programs have been in place for years. For those who are passionate about these issues, more can and should always be done. The question is whether or not public opinion will shift enough for there to be broad pressure on the Stampede to take further steps, and whether it will choose to be proactive or reactive.

Other cultural shifts may also affect the Stampede in years to come. The idea of rodeo queens and princesses feels increasingly clunky in the #MeToo age. Calgary’s energy-dominated corporate culture is also due for an evolution, with the oil-boom years possibly behind us. What would it mean for the Stampede to lose the adjacent corporate parties and events, or the many tickets purchased by these large companies?

Stampede is a massive year-round presence in Calgary, with an influential board of directors, hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue and arguably the strongest brand in the city. And the annual festival continues to draw enormous crowds — Connell notes that the Stampede had two of its best three years for attendance during the latest economic downturn. The sun is hardly setting on Weadickville.

But even if it doesn’t face imminent threats from cultural and demographic shifts, the Stampede, just like any organization, must take a long view to secure its future. Our leading cultural institutions must all continually strive to be better. Turning a ship the size of Stampede, even a few degrees, takes time.

“Frankly, I don’t think you could erase the Stampede,” Robinson says. She believes the organization is capable of reform — both in terms of what it presents at the annual festival as well as the makeup of its board — but she worries the public pressure needed to force those changes comes with a risk. “Arguably the Stampede board is the most influential board in the city,” she says. “And anybody saying anything negative about it is [committing] political suicide.”

For her part, Gondek hopes for a future role for Stampede as more of an actively engaged participant in city life throughout the year, and she would like to see the organization exercise some of its great power to speak up for civic-minded causes, even by presenting at council. Given the wealth of performing arts that call Stampede Park home — from the Young Canadians and the Grandstand show to the Calgary Arts Academy and, soon, Calgary Opera — she believes the Stampede should lend its considerable voice to support causes it aligns itself with.

“My conversation with Stampede has been: How come you guys never come forward in support of the arts when we’re debating this stuff at council? And they said, ‘Oh. Well, we didn’t know we were supposed to,’” says Gondek. “It’s not whether you’re supposed to, but you should, because you are actively doing something to engage youth and promote the arts in our city, but no one really knows you’re doing it.”

Gondek says she thinks it’s also up to city council to invite that voice in because, as it is, Stampede purposely doesn’t want to be seen as influencing politics. “Stampede has been a standalone entity for so long, and it’s been such a machine in and of itself. It’s time to get them out of that mode of operating on their own and actually make them a part of our city properly,” she says.

Macmichael, who has a good working relationship with the Stampede, is a big believer in the idea that the organization promotes community and plays an important role in the city, both economically and culturally. But he also sees evolution as an imperative. “That’s the balancing act that Stampede is sort of wrestling with: How do they stay true to their history while bringing in more of the community that represents the whole of Calgary and not just the white, Western cowboy culture — but brings them in a way that allows them to experience and appreciate the history without feeling excluded by it?”

He sees an analogy in the story of another big organization. “Kodak thought it was a film company, but it was really a memories company,” says Macmichael. Clinging for too long to the sentimentality of its film business and failing to adapt to changing times led it to file for bankruptcy in 2012. Macmichael believes the Stampede still sees itself as centred around the rodeo. “And sure, that’s what they are, in some respects, but I think if they remember that they’re about community and gathering to exchange thoughts and commerce and a good time, they’ll be around forever.”

For Connell, the future is encouraging, and he believes his organization is flexible enough to adapt to the changing times. “I think what’s important is that the Stampede does continue to listen to its community and remain relevant, and that will take a number of forms based on the community,” he says. “So yes, our events at the grandstand may look different when it comes to rodeo or chuckwagons, it may look different in agriculture in what we’re promoting as part of agriculture, or renewable energy.”

But some things will remain the same, he says. The Stampede will still be The Stampede. “I think Calgarians are very proud of what they define as Western heritage and values, and I think that’s important. We don’t define that for them. Everybody has their own version of what that is.”

And that makes it harder than ever to be all things to all people. But maybe it does make it possible for the Stampede to keep being enough things to enough people to remain durable for years to come.